Key points:

- The Rev. Bruce W. Robbins was an advocate for Christian unity and interfaith dialogue. He died Aug. 3 at age 73.

- Bishop Sally Dyck, who was Robbins’ bishop in Minnesota, remembered how Robbins always kept ecumenism “front and center” in the work and witness of the church.

- Robbins credited Mother Teresa with changing his life and setting his course in ministry in The United Methodist Church.

- He was a longtime advocate for LGBTQ rights and never stopped pushing for dialogue both ecumenically and among United Methodists with theological differences on the issue.

When anti-Muslim feelings flared after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the Rev. Bruce W. Robbins counseled his fellow United Methodists “not to bear false witness against your neighbor” or “judge another tradition by its worst practitioners and yours by its best.”

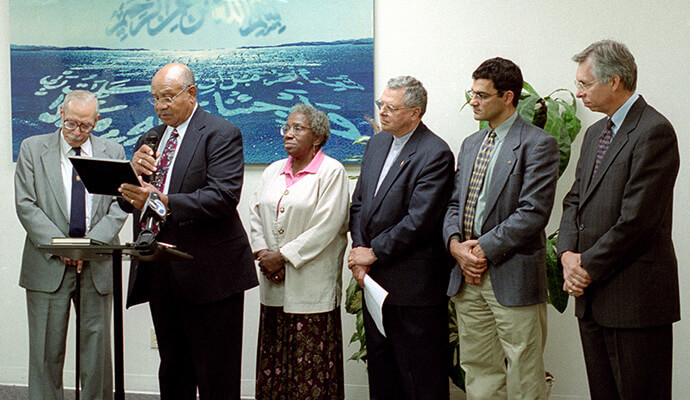

And then, a month later, Robbins arranged for directors of the denomination’s Commission on Christian Unity and Interreligious Concerns to visit the Islamic Center of Southern California as part of a previously scheduled board meeting.

That was who he was: a committed ecumenist who embraced connections with all religions.

Robbins, 73, died Aug. 3 at his home in Minneapolis.

He held both staff and top leadership roles with the Commission on Christian Unity and Interreligious Concerns from 1986 to 2004 and then served as senior pastor of Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church in Minneapolis until his retirement in 2013. His focus on church unity also supported full inclusion for LGBTQ members.

His world was as large as the global gatherings he participated in and as small as the church in East Barnard, Vermont, where he preached and served as the music leader for many summer seasons.

Jan Love — who met Robbins in 1975 when both were graduate students attending the World Council of Churches Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya — was part of those ecumenical circles. She called Robbins “an extraordinary leader in so many ways.”

“He had a profoundly positive impact on the church and was one of the church’s bright and shining lights,” she told UM News.

Robbins had been living with multiple myeloma and was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in June 2023, according to his children, Adam and Casey Robbins. Other survivors include his sister, Betsey Norgard, and her husband, Alan; two grandchildren, Hannah and Benjamin Robbins, and Adam’s wife, Jennifer Ghusson.

The United Methodist Council of Bishops paid tribute to Robbins as “a visionary and bold leader.” He was ordained a deacon in 1974 and an elder in 1981 and held degrees from Union Seminary and Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University.

Bishop Sally Dyck, who was his bishop in Minnesota and recently served as the denomination’s ecumenical officer, remembered how Robbins always kept ecumenism “front and center” in the work and witness of the church.

“He was just an incredible advocate,” she told UM News, “and always had a teaching moment.”

Bishop Karen Oliveto got to know Robbins when he served as a “very active” board member of the Reconciling Ministries advocacy group. “I was always struck by his clarity that the church should be an inclusive place for all of God’s children,” she said.

“His gentleness and his compassion always stood out for me,” Oliveto added. “That’s what his wisdom was wrapped in.”

Robbins was born on April 29, 1951, in Brooklyn, New York, to William A. Robbins, a United Methodist minister, and Doris Robbins, a nurse, and spent his childhood in upper New York State. He attended Oberlin College and Union Seminary and, like other young people, became involved in social justice issues.

Robbins’ experience at the 1975 Nairobi assembly led to the realization that his call to ministry would involve ecumenical work. But it was the volunteer work later that year with the Missionary Brothers of Charity in India, associated with Mother Teresa, “that shaped the faith that would sustain me in the ministry to come,” Robbins wrote years later in a 1997 column for The United Methodist Review.

Memorial service

He credited Mother Teresa with changing his life, which “set my course in ministry in The United Methodist Church.”

Those early experiences established a thread of pilgrimage and “search for wonder” that his children said continued throughout his life. Even in his later years, Adam Robbins noted, their father — who kept daily journals and surrounded himself with books on Methodist history and art — was still traveling and learning. He also found purpose as a docent at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

“He had this expectation almost of mystery,” said daughter Casey Robbins. “He really believed in the ways in which the world would surprise or startle you into grace.”

The grace that Robbins witnessed during his time with Mother Teresa informed his advocacy as the HIV/AIDS crisis grew in the 1990s.

The Rev. K Karpen, pastor of the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew in New York, where the Robbins family worshipped, recalled a sermon that Robbins preached there, tying “that experience (with Mother Teresa) to the need of the church to respond to and embrace those who were suffering and dying of AIDS,” Karpen said.

Robbins also traveled with the Rev. Don Messer, longtime champion of the United Methodist Global AIDS Committee, to India in 2003 to provide HIV/AIDS education and distribute gifts to HIV hospital patients in Calcutta and Chennai.

“He was ahead of most people in terms of openness to other religions and other denominations in the ecumenical sphere,” said Messer, who called Robbins gentle and kind “and always liberal and brave in his statements.”

Robbins was a longtime advocate for LGBTQ rights and never stopped pushing for dialogue both ecumenically and among United Methodists with theological differences on the issue.

As commission members from 2000 to 2004, Messer and Love both worked with Robbins on a denominational task force to set up dialogues on homosexuality and the unity of the church from a theological perspective. “We had many forums trying to bring evangelicals and progressives together in the church,” Messer said.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

That commitment continued through the rest of his life. In 2013, when Bishop Melvin Talbert was facing pressure from other bishops for agreeing to officiate at a same-sex wedding, Robbins defended him in a UMNS commentary and made a plea to “keep listening and loving one another” within the denomination.

Robbins hosted an interfaith news conference in 2012 at Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church that announced the formation of Clergy United for All Families, which was working to defeat a marriage amendment on Minnesota’s ballot that would write a law defining marriage as one man and one woman into the state constitution.

Love recalled Robbins’ desire to “honor the light of Christ” in those with whom he disagreed.

“We both deeply believed that one of the values of a Christian life is to listen deeply and closely for each person’s understanding of the faith and the way that they experience the reality of Christ in their daily life,” she said.

But Robbins also had deeply held values, including his position on full inclusion in the church. “He kept those two sets of values in productive and creative tensions so he could fully live out his commitment to both,” Love said.

Bloom is a retired UM News assistant news editor. She lives in New York.

News media contact: Julie Dwyer at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.