Key points:

- During his lifetime, Lawson studied and taught nonviolent resistance, walked with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and trained many of the young leaders of the Civil Rights Movement.

- The son and grandson of Methodist pastors, Lawson received his local preacher’s license in 1947 when he graduated from high school.

- While a pastor at the Centenary Methodist Church in Memphis, Lawson invited King to support their efforts in the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike. King delivered his “Mountaintop” speech on the eve of his assassination.

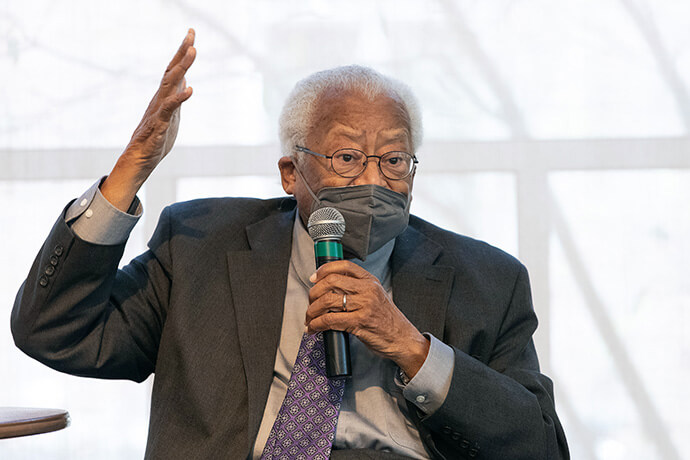

The Rev. James M. Lawson Jr., who made it his life’s work to create a nonviolent nation, died June 9 at age 95.

During his lifetime, he studied and taught nonviolent resistance developed by Mohandas Gandhi, walked with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and trained many of the young leaders of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

“I always found Rev. Lawson to be a font of wisdom, instruction and inspiration,” said Dennis C. Dickerson, the Rev. James M. Lawson chair of history emeritus at Vanderbilt University. Dickerson is writing a biography of Lawson.

“He remained consistent in terms of his anti-militarism, his pursuit of peace, his pursuit of non-violence and his pursuit of loving people, regardless of class, color or region.”

Lawson kept his deeply held faith that nonviolence is the way to peace when he elected to be a conscientious objector of the draft during the Korean War and was jailed for 13 months while he was a student at Baldwin Wallace College in Berea, Ohio. He was arrested for organizing lunch counter sit-ins and other nonviolent protests in 1960 in Nashville. His civil rights activity got him expelled from Vanderbilt Divinity School.

Lawson, the son and grandson of Methodist pastors, received his local preacher’s license in 1947 when he graduated from high school. He was introduced to the nonviolence teachings of Gandhi when he joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation, America’s oldest pacifist organization, during his college days. He spent three years in India as a missionary.

While in graduate school at Oberlin College in Ohio, he was introduced to King.

Lawson introduced the principles of Gandhian nonviolence to young leaders of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. In his training of pastors, Lawson said, “Gandhi was not our major teacher, Jesus was.” He moved to Nashville to attend Vanderbilt University at the urging of King.

He trained many of the future leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, including John Lewis and C.T. Vivian. Lawson was among the speakers at Lewis’ 2020 funeral.

“Jim Lawson taught 20th-century Methodists how to do nonviolent protest,” said Ashley Boggan D., top executive of the United Methodist Commission on Archives and History. She noted that many United Methodist women also protested segregation.

“A lot of Methodist women were doing protests in different ways, but I would say Jim Lawson taught Methodists how to do public acts of nonviolent protest.”

When he was expelled from Vanderbilt University in 1960, United Methodist-related Boston University invited him to come finish his studies there. Lawson said they told him, “just come and we’ll accept all your credits, we’ll grant your degree. That was critically important.” He received his Baccalaureate in Sacred Theology from Boston University.

“He could make you take off any rose-colored glasses you had on, and at the same time … really, really believe that change is possible,” said Phillis Isabella Sheppard, executive director of the James Lawson Institute for the Research and Study of Nonviolent Movements at Vanderbilt.

“I found it inspiring, even enjoyable, the way in which he was an intelligent, informed person committed to direct action.”

Lawson helped coordinate the 1961 Freedom Rides and the Meredith March in 1966.

While a pastor at the Centenary Methodist Church in Memphis, Lawson invited King to support their efforts in the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike. King delivered his “Mountaintop” speech on the eve of his assassination.

Decades later, Vanderbilt welcomed Lawson back as an honored professor, and in 2022, the university honored him with the launch of the institute in his name.

“Rev. Lawson was an American hero,” said Daniel Diermeier, chancellor of Vanderbilt. “Without his spiritual guidance, moral example and deep understanding of the principles and practices of nonviolent protest, the Civil Rights Movement as we know it might not have existed.”

Diermeier added that the grace Lawson extended to Vanderbilt after his expulsion shows “a way forward still.” Lawson donated some of his papers to Vanderbilt, and returned to teach several times. He was also on the advisory committee for the Vanderbilt institute that studies nonviolence.

King called Lawson “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

“One of the things that Gandhi taught me, by my study and research, is that nonviolent power is the creative power of life itself and the power that produced our universe and human life,” Lawson said in a 2022 interview with United Methodist News.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

Lawson also spoke with United Methodist News in 2016 while he was in Clinton, Tennessee, participating in the Children’s Defense Fund’s Proctor Institute. He was a consultant for the Children’s Defense Fund for several years.

At that time, he talked about an incident in his childhood that he said put him on the right path.

He had his first encounter with racism on a street in Ohio. A young white child sitting in a car leaned out the window and hurled the “N” word at him.

“I went over and slapped the boy and went on home,” he said. He sat down at the kitchen table — his mother was working on dinner, and he told her about the incident.

“Without turning to me she said, ‘Jimmy, what good did that do?’”

On that afternoon, his mother gave her young son a lesson he never forgot about what it means to be a child of God, loved by Jesus. She told him that name-calling could not possibly harm him.

“And her last sentence was, ‘Jimmy, there must be a better way.’ And so in many ways that’s the pivotal event of my life,” Lawson said.

Lawson served as pastor of Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles from 1974 until his retirement in 1999. He remained on staff as pastor emeritus until his death.

He served at Scott’s Chapel, Shelbyville, Tennessee, from 1960 to 1962 and Centenary United Methodist Church, Memphis, from 1962 to 1974.

He never retired from fighting for civil rights and continued to speak, teach and inspire young minds.

“I don’t think he ever wrote a memoir because he never thought his work was finished,” Dickerson said. “Now, that’s my speculation. … But being around him, that’s the conclusion that I reached.”

Lawson wrote Revolutionary Nonviolence, Organizing for Freedom, published in 2022.

In 2023, James Lawson High School, named in his honor, opened in Nashville, Tennessee.

In 2024, a portion of Adams Boulevard in South Los Angeles was named the Reverend James Lawson mile.

“I would just say that his loss is heaven’s gain,” said the Rev. Adrienne Zachary, lead pastor at Crossroads United Methodist Church in Compton, California. “The legacy of social justice advocacy is a mantle that he has passed on to me and my ministry.”

Zachary said she was trained by Lawson in civil disobedience.

“I pray to be as fruitful and faithful as he has been.”

Gilbert is a freelance writer in Nashville, Tennessee. Jim Patterson is a reporter with UM News. News media contact: Julie Dwyer at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.