Key points:

- The biennial National Summit on Mass Incarceration and Social Justice took place Oct. 2-5. Participants heard from speakers and learned about the issues around mass incarceration.

- The top executive of Strengthening the Black Church for the 21st Century shared how he is personally affected by the justice system.

- Missouri Conference leaders noted the execution of Marcellus Williams, a convicted murderer who was put to death on Sept. 24 in the state, while doubts about his guilt persisted.

Story after story of the heartaches caused by mass incarceration in the United States were leavened by tales of redemption — former inmates now thriving in the outside world.

There was Kemba Smith’s redemption story, which kicked off the biennial National Summit on Mass Incarceration and Social Justice. It’s a compelling one, strong enough to merit its own short film.

Participants also heard from the Rev. Stephen Barbee, an All-American college football player who lost his freedom because of substance use; and Missouri state Sen. Barbara Anne Washington, a self-proclaimed “nerd” who as a 13-year-old used a knife to defend herself from a schoolboy, and ended up in jail after he died.

And overhanging the summit was the case of Marcellus Williams, a convicted murderer who was put to death on Sept. 24 in Missouri, while doubts about his guilt persisted. Williams served as a kind of patron saint for the summit.

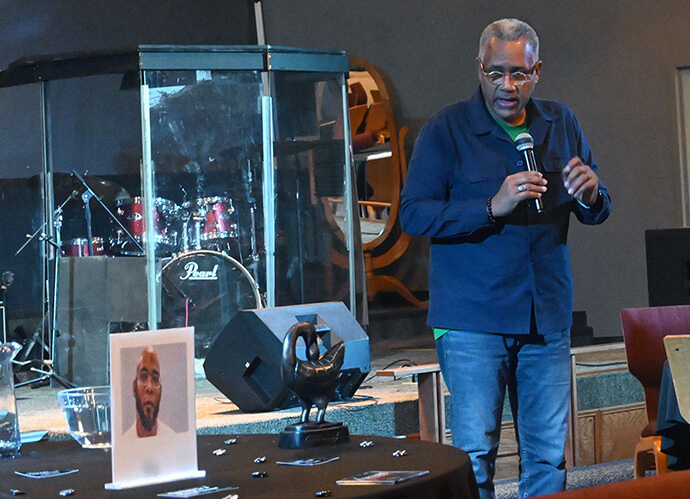

All those are gripping and sometimes triumphant tales. But it’s another unfinished story that weighs on the Rev. Michael L. Bowie Jr., the national executive director of The United Methodist Church’s Strengthening the Black Church for the 21st Century, the group that organized the summit Oct. 2-5 at St. James Church, a prominent United Methodist congregation. It involves his own family.

After Bowie saw the film about Smith’s imprisonment and visited two organizations that were committed to reentry and decreasing recidivism, he decided to take a break from his own summit to regroup. His son, Michael L. Bowie III, known as “Trey,” is being held in a county jail for drug possession. He could get two years — but due to his mental illness, his parents are hoping for probation.

“This is probably one of the deepest hurts that I’ve ever experienced in ministry. It’s deeper than membership declining or deeper than not meeting budget,” said the elder Bowie.

“We’ve been having challenges with our son, who’s bipolar and not consistent in taking his meds,” he explained. “He’s been in and out of rehab facilities for self-medicating his disease. He has a great heart and is a smart kid, but it came to a point where we had to just let go and trust God.”

So Bowie, who is used to “preaching and encouraging others,” found himself the one needing to be encouraged. “I often remind those who are experiencing challenging moments in life that ‘trouble don’t last always,’ and now I have to preach that to myself.”

The summit attracted more than 50 participants from six annual conferences in The United Methodist Church, to network and learn about the issues around mass incarceration. In addition to Strengthening the Black Church for the 21st Century, sponsors included United Women in Faith, United Methodist Discipleship Ministries and the denomination’s General Council on Finance and Administration.

“The United States incarcerates more people, in both absolute numbers and per capita, than any other nation in the world,” the American Civil Liberties Union reports. “Since 1970, the number of incarcerated people has increased sevenfold to 2.3 million in jail and prison today, far outpacing population growth and crime.”

One of every three Black males will go to prison during their lifetime, again according to the ACLU.

At the summit, participants heard from people who are frustrated by the U.S. justice system, especially its emphasis on imprisonment as the answer to crime.

Eighty-three percent of prisoners who get out will return to prison, according to summit speaker Brian Roper, the founder and CEO of One Life Second Chance Inc. in Kansas City, which tries to help released prisoners become successful members of the community after their release.

“If we say the system’s working — working for who?” Roper said. “Well, there’s some investors who are tied to the system that love the fact that we have the largest incarcerated population in the world.”

There are other ways capitalism supports mass incarceration, said Nicole Price, the CEO of Lively Paradox, a company that coaches people and organizations on leadership.

“If you think about Securus Technologies, I love that they exist,” Price said. They make it possible for me to do a video call with my nephews who are in prison. But, last year, they made $700 million. So, is it beneficial to them for there to be less people in prison? Not at all, not at all. They make more money when there are more people in prison.”

Likewise, companies that sell uniforms to prisons and others who benefit from work-release programs do better the greater the prison population, she said.

“We have to understand how all of these things work together,” she said. “Because even though we wouldn’t operate that way, many people do.

Keeping former inmates from going back to prison is a complex challenge.

Crossroads United Methodist Church in Compton, California, offers an expungement clinic, which helps formerly incarcerated individuals get their criminal records cleaned up so they have a better chance to land a job.

“How many are aware of the collateral consequences of criminal conviction?” asked Sam Hough, associate pastor at Crossroads who has done time in prison.

Hough said there were more than 40,000 restrictions around the country including bans on buying a house and participation in homeowners’ associations, renting an apartment, qualifying for credit and getting professional licenses for occupations like cutting hair.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

In some instances, the system inadvertently pushes former drug users back to the habit, Hough said.

“I’ve known too many people who were using just enough drugs to test dirty so that they qualify for the substance abuse housing program,” he said. “So, the choice is face being homeless or go back to something they have kicked. Their intentions were simply to not be homeless, so when we look at reentry housing, it’s a huge issue.”

Hough told a story of a friend who learned how to make lenses for glasses and did it for years while in prison. When he got out, he could not get a license to work in that field because of his criminal record.

The summit ended with a ceremony to honor Williams.

“We thought it’d be appropriate to remember brother Marcellus Williams, who was executed right here in the state of Missouri,” Bowie said. He added that Williams’ execution by lethal injection “was a profound miscarriage of justice and a grievous moral failure.”

The Rev. Emanuel Cleaver III, senior pastor of St. James Church, said that Williams was “held captive by a system that needs to be changed.”

“In Luke 4:18, Jesus began his earthly ministry by reading the words of the prophet Isaiah on a scroll in the synagogue, proclaiming to set the captives free,” Cleaver said. “Then he began his ministry of setting people free from illness, setting people free from emotional harm, setting people free from sin.

“That’s why we’re here today, because we are followers of that teaching to work, to set free from unjust sentencing, free from wrongful convictions.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more, subscribe to the free UM News Digests.