Key Points:

- The Rev. James M. Lawson passed away June 9 at the age of 95.

- He is being remembered as a “giant for nonviolence, peace and love.” Acolytes and friends of the civil rights leader say his legacy will continue to change society for the better.

- In addition to his work in the Civil Rights Movement, Lawson was a staunch United Methodist who made ecumenical work a priority.

The story of the Rev. James M. Lawson Jr. and the biker may be apocryphal, but his friend and former parishioner Clara Ester says it’s true.

One day a burly white guy in a Harley Davidson leather jacket, presumably not a fan of the Civil Rights Movement, spat in the civil rights leader’s face.

“Jim Lawson looked at the guy and in conversation asked him if he rode a motorbike,” said Ester, a member of Lawson’s congregation at Centenary Methodist Church in Memphis, Tennessee, in the 1960s. “The guy indicated, ‘Yeah.’ Then he asked him what type, and did it have those things on the back of it that made all that noise?”

The conversation continued, and Lawson offhandedly asked the biker if he had a handkerchief he could borrow.

“And (the biker) pulls out his handkerchief and hands it to Jim to wipe his spit off of Jim’s face,” Ester said. “The average person that would be spit on, you would have to catch yourself really hard and quick not to respond back to that kind of treatment.

“That young man, if he is still alive, has to be a different person to continue to be in a conversation and to offer a handkerchief to somebody that you’re confronting around racism. (Lawson) was a giant for nonviolence, peace and love,” she said.

“He lived the life he requested of us to live.”

There are many such stories about Lawson, one of the last remaining Civil Rights Movement leaders. He died June 9 at age 95.

“There’s a story … about a student trained by Lawson and somebody walked up and used the N-word, and told him he was going to either beat him up or kill him,” said Tex Sample, the Robert B. and Kathleen Rogers Professor Emeritus of Church and Society at Saint Paul School of Theology.

“The student responded in accord with Lawson’s teaching,” Sample said.

“‘I can’t keep you from killing me, but I can assure you, you will not make me hate you, and I will continue to love you,’” the student replied.

“Wow,” Sample said. “I think that was so deeply characteristic of Lawson.”

Lawson’s life was eventful. He was introduced to passive resistance as a boy by his mother, lived in India for three years to study it and trained many of the students who used it to fight Jim Crow laws at the request of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. And that’s just a small sampling of his accomplishments.

“I love that he got to live a long, full life,” said Yolanda Pierce, dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School. “Unfortunately, so many of his peers did not. There were so many early deaths, … so I am just so humbled by the fact that we got to have him in this world for the 95 years.”

Overshadowed among his achievements was his interfaith work, Pierce said.

“I don’t think that we really talk enough about the kind of interfaith work that he did, the ways in which he situated himself to understand other people’s faith,” she said. “It feels like we’re in that same historical moment where that is what we need.”

Also sometimes overlooked was Lawson’s prison term for refusing to serve in the Korean War, Sample said.

Lawson “was a conscientious objector and went to prison for a year when he was a very young man,” Sample said. “He was so committed to nonviolence that he was not going to participate in that.”

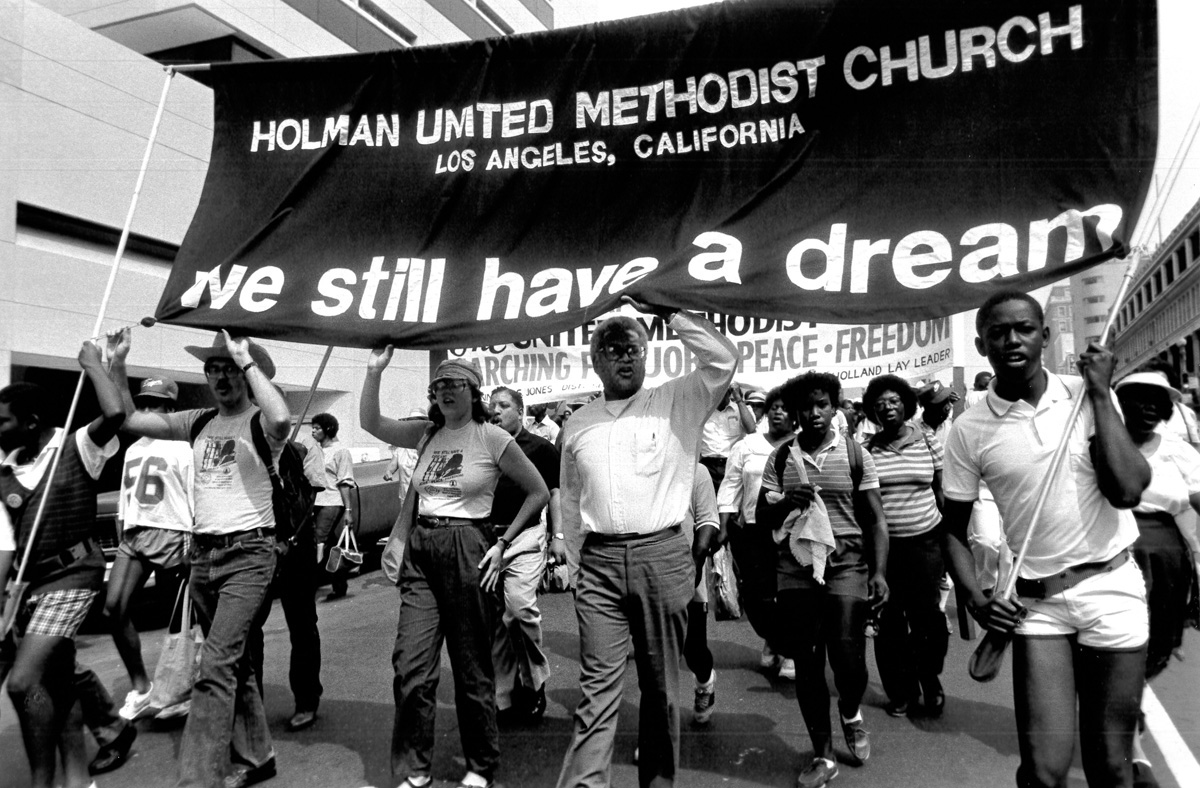

In addition to activism, Lawson pastored United Methodist churches, the last being Holman United Methodist in Los Angeles. He promised his congregations that his political activities would not interfere with his pastoral duties, and made good on the promise, said Dennis C. Dickerson, the Rev. James M. Lawson chair of history emeritus at Vanderbilt University.

“Jim was a staunch Methodist,” said Dickerson, who is writing a biography of Lawson.

“He often cited the works and the ideas of John Wesley and said one time he was often amused because people thought that he was a Hindu mystic, because he was just so open as far as ideas and ethics and all of that, but he was a dyed-in-the-wool Methodist, a real son of John Wesley.”

The Rev. Michael L. Bowie Jr., top executive of United Methodist Strengthening the Black Church for the 21st Century, said The United Methodist Church “lost another giant, another soldier for justice.”

“He was an advocate for the marginalized,” Bowie said. “He was very passionate about the Black church. He was a brilliant thinker. He was an advocate for the nonviolent movement. He was a strategic leader.”

Only Bayard Rustin equaled Lawson as a strategist for the Civil Rights Movement, Sample said.

“James Lawson is a greater human being than any president we’ve had in my lifetime,” said Sample, who goes back to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

“I’m talking about in terms of greatness as a person,” he added. “We can argue about their impact.”

Despite his accomplishments, Lawson remained modest, Dickerson said.

“I thought unnecessarily modest, if I could say that,” he said. “He was not puffed up. He just did not have that kind of ego that others have.”

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

Younger Black United Methodists and others are striving to continue Lawson’s work, several of them said.

At the James Lawson Institute for the Research and Study of Nonviolent Movements at Vanderbilt University, his ideas will be taught to future generations, said Phillis Isabella Sheppard, an ordained priest with the Association of Roman Catholic Women Priests, who runs it.

“We’re continuing to do our training where folks learn the philosophy and method of nonviolent direct action,” Sheppard said. “Ideally, what will happen over the next year, we will have a certificate that draws on the schools of the university on nonviolence.”

At First United Methodist Church of Inglewood in California, a groundbreaking on affordable housing for 60 families is coming, said the Rev. Victor Cyrus, pastor of the church.

“In my sharing with Rev. Lawson, seeking his advice and counsel, he said that is very much aligned with the nonviolence movement,” Cyrus said. “When we talk about creating a society of non-injury, a society that is not violent, a society that is restorative for all of God’s people in all creation, having housing that all people can afford aligns with that, along with health care, along with Head Start for young people to have access to education.”

Cyrus starts a new assignment July 1 at Holman, Lawson’s last appointment.

At Crossroads United Methodist Church in Compton, California, the Rev. Adrienne M. Zachary runs a ministry inspired by Lawson to help prisoners thrive after release.

“The prophetic preaching and witness that I saw and observed from Dr. Lawson … was applicable and relevant in the ministry that I have now,” she said. “Those theological premises of justice and compassion … became real and relevant to me in my ministry, and the way that I serve here.”

East Ohio Conference Bishop Tracy S. Malone, the first Black woman to be president of the United Methodist Council of Bishops, said in a statement that Lawson’s “passion for justice, equality and fairness have impacted many people’s lives and communities.

“Some of us would not be in the roles we serve today had it not been for such powerful leaders such as Rev. Lawson, who paved the way for us.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.