Key Points:

- People on their way to sobriety find a safe place to heal at the Lucille Raines Residence, which is operated by United Women in Faith of Indiana.

- Carolyn Marshall, former secretary of General Conference, runs the program with the help of former addict Mariea Strader. The home is in a former Indianapolis hotel and offers a supportive, dorm-like atmosphere.

- The residence is currently collecting donations to pay for a new boiler.

If you were walking down a dark city street and saw Jeremiah Bowden coming your way, you would probably feel intimidated. Or just plain scared.

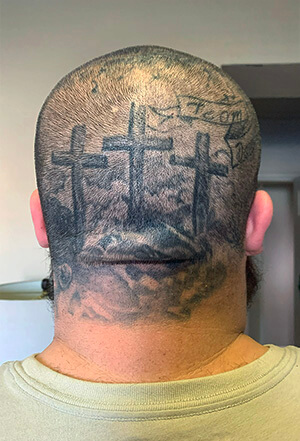

Bowden, 33, is a burly guy with tattoos up and down his arms and on his face as well. In the light of day, his gentle eyes soften the effect. But you wouldn’t see that after sundown.

“It’s stressful,” Bowden said in an interview at the Lucille Raines Residence, where he lives. “It gives me anxiety, too, because I just feel like everybody’s just watching me, and I’m not even doing anything wrong.”

There was a time, not all that long ago, when keeping one’s distance from Bowden was a good judgement call.

“When I was on drugs, I was a horrible person,” he said. “I didn’t care about anybody’s feelings other than mine. If I didn’t have anything to gain from it, I didn’t care for it.”

Bowden, who now helps other recovering addicts as a counselor, has a biography comparable with the Biblical Job, whom God tested with horrible, escalating trials. It started when Bowden was bullied as a child. From there, he endured his dad committing suicide and his stepdad and mother succumbing to cancer.

That’s enough tragedy for anyone, but Bowden endured more.

He also discovered the body of his brother, who had died from an overdose. As a teenager, a defensive violent act led to his imprisonment.

“I ended up doing six years,” he remembers. “I got out on my 18th birthday.”

If you saw Carolyn Marshall coming your way, you wouldn’t feel threatened at all. She is an 88-year-old woman whose placid appearance belies a steel spine. She has held leadership positions in The United Methodist Church for decades, most prominently as secretary of the General Conference for 16 years.

That position put her in charge of orchestrating the church’s top legislative assembly every four years, where leaders debate and chart the denomination’s direction. It’s a mammoth undertaking where small mistakes can lead to chaos. She can tell war stories like the 1992 General Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, when the convention center wasn’t ready as expected.

How to help

“They went out to RadioShack and bought all the wiring that there was in Louisville,” she remembers.

The journeys of Marshall and Bowden intersected at the downtown Lucille Raines Residence, which is owned and operated by United Women in Faith of Indiana. Marshall is executive director of the “three-quarter house” for recovering addicts in transition after in-patient treatment. The now-clean Bowden is living there while he works to get his life together and counsels other addicts.

The program, at a building that used to be the Nottingham Court Hotel, hosts nearly 50 residents like Bowden. It was founded in 1977 when a Salvation Army program needed a home and The United Methodist Church had the building, which it wanted to put to use.

“Those of us who know The United Methodist Church upside down and backwards think we have structure that gets in the way sometimes,” Marshall said. “But I can tell you, the Salvation Army’s got more structure than we know how to talk about. They are really structured, and so getting everything through them was a problem.”

But the United Methodist-Salvation Army mash-up came together under Marshall’s leadership. The Lucille Raines name honors the late wife of former Bishop Richard C. Raines, who led The Methodist Church in Indiana from 1948 to 1968.

Mariea Strader was once a client of the residence and has her own tales of her circuitous route to sobriety. Today, she is program coordinator and Marshall’s second-in-command. Strader says the rules there are straightforward.

“We get most of our clients and residents from recovery houses after they complete their program,” Strader said. “After I interview them, if they qualify to come here, they have to have a job, be working with a sponsor and going to 12-step meetings.”

Residents are asked to stay for at least a year, but there is no hurry to make anyone leave after that.

“As long as they’re doing what they need to do for themselves, we allow them to stay,” she said. “Some of them, they come here, they don’t have family and it’s just them … and they feel like this is their home. If they have children or marriage, after they commit their year, they go back to their families.

“But we don’t rush them normally.”

As part of the effort to build confidence, the 12-step meetings are attended off-site.

“We’re trying to get them self-sufficient, where they’re rebuilding their life,” Strader said. “If they’re depending on here, then they get complacent. They’re supposed to be gradually moving back into society, so the best thing to do is go outside of the building.”

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

The accommodations aren’t luxury living — more like a college dorm. Only recently the elevator was reopened for the first time since May 2023, because it took time to raise the $750,000 needed to fix it. Now money is being collected to pay for a new boiler, which had to be replaced after it sprang a leak.

Although he does want to get his own place when possible, material comforts aren’t high on Bowden’s priority list just yet.

One goal for the former imbiber of methamphetamines, ecstasy and heroin is to stop “misunderstanding boredom with peace.”

“I would always be bored, and when I was out there getting high, it was a hectic lifestyle with everything happening,” he said. “I think that’s the part that I missed the most, but now I have come to terms with being at peace instead of considering it boredom, and that helps me tremendously.”

Bowden has entertained thoughts of becoming a pastor.

“When I was younger … I really didn’t care for church, because I didn’t really understand the concept of God,” Bowden said. “Then, losing my mom and my brother and my stepdad, I just thought, like, God hated me.

“It came down to the point where I was going to commit suicide,” he said. “I did that foxhole prayer, like ‘God, if you are who you say you are, help me.’”

Bowden said that was the point where his life started to incrementally improve.

“I started reading the Bible more and I started going to Bible studies,” he said. “I started going to church and to really be passionate about my religion, and today, I don’t think I would be here if it wasn’t for God.”

Going forward, Bowden says he would like “a nice home and a nice family to come home to from a nice job. I would like to go on vacation. I would like to see different parts of the world.”

But for now, he’s happy to be working toward all that at Lucille Raines, and being an asset to people who used to be where he was.

“Right now my life is way better than what it was, so I’m kind of content with it,” Bowden said. “But the best kind of accomplishment is to help somebody else.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.