Key Points:

- The Rev. Andy Oliver knew he had to change his life when he suffered a heart attack in his early 30s.

- His journey from burnt-out pastor to passionate activist has taken some interesting stops, including public relations and tending bar.

- Now back in church ministry, Oliver and a colleague are leading weekly protests at detention centers in the state that are housing suspected undocumented immigrants.

A heart attack in his early 30s jolted the Rev. Andy Oliver so badly he quit his ministry and worked as a bartender while he “figured things out.”

“The doctor said, ‘Your arteries were clear. Are you under a lot of stress?’ At that point, I decided to take medical leave,” said Oliver, today back in church ministry as pastor of Allendale United Methodist Church in St. Petersburg, Florida.

“In my first two appointments, I did my best to be careful and to toe the line, to not say anything that would prevent my promotion in the institution of the Methodist Church,” Oliver said in an interview with United Methodist News.

A letter from a colleague and Oliver’s reluctant decision to decline to conduct a wedding ceremony for two gay childhood friends because of United Methodist rules were too much. He quit the ministry.

“What really moved me was a letter I received from a seminary colleague,” he said. “He had come out (as gay) in seminary, and I watched his family and his church kind of disown him and turn their back on him.”

Then Oliver had the heart attack in September of 2012 and walked away from all of it.

“I tended bar for a while to figure things out, and a person who is … queer found me.”

That person was Felipe Sousa-Lazaballet, an immigrant rights activist and executive director of the Hope Community Center in Apopka, Florida.

Sousa-Lazaballet had read Oliver’s blog, liked what he saw and wanted to train him to be a community organizer.

“(Sousa-Lazaballet) said Jesus was a community organizer, and he was a pretty good one because we’re still talking about him,” Oliver said. “He taught me the principles of community organizing.”

Next, a chance meeting led to Oliver doing public relations work for Reconciling Ministries Network, which advocates for full inclusion of LGBTQ people in The United Methodist Church.

“That’s around the time of the General Conference in Tampa, (Florida),” Oliver recalled.

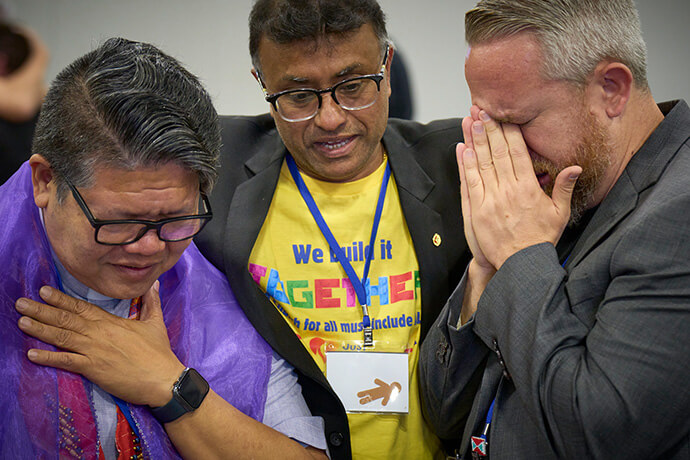

Near the end of the 2012 event, about 300 protesters interrupted, singing and chanting on the conference floor in response to the “derision and scorn” they said that LGBTQ attendees experienced during a discussion of the denomination’s position on LGBTQ inclusion. The position, eliminated at the 2024 General Conference in Charlotte, North Carolina, was that “the practice of homosexuality … is incompatible with Christian teaching.”

“I was watching on the livestream from Lakeland (Florida), and I felt a second calling back into the church,” Oliver said. “I was weeping, and I drove over to Tampa, which is a short distance from Lakeland, and I happened to sit next to someone who worked at Reconciling Ministries Network.”

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

A few months later, Oliver was hired by the advocacy group.

In 2016, he returned to pastoral ministry with an appointment to Allendale.

“I think Andy was given a beautiful gift, wisely discerned by our previous bishop, Bishop (Kenneth) Carter, to give Andy the opportunity to serve at Allendale and to basically move into a community that has a high population of both LGBTQ folks, but also an African American community,” said the Rev. Roy Terry, who pastors Cornerstone United Methodist Church in Naples and is a longtime friend and mentor of Oliver.

“(Allendale) tends to be a little more progressive than some other places in our state,” Terry said. “And the bishop basically said, ‘Hey, Andy, go do what you do.’

“And he did.”

Back as a pastor, Oliver was profoundly impacted by a book released this year by Ashley Boggan, top executive of United Methodist Archives and History. The book is “Wesleyan Vile-tality: Reclaiming the Heart of Methodist Identity.”

“(John) Wesley was called vile for being with people on the margins and for showing up in spaces that other people thought was beneath him,” Oliver said of the founder of Methodism.

“Those are the spaces I feel called to be, and so the fact that I get to be at Allendale and be a part of a community that is living that out is just really special.”

There have been costs to his activism. Oliver could get a year in jail after being arrested Aug. 29 and charged with misdemeanor obstruction for kneeling on a Black History Matters mural to protest efforts of Florida Department of Transportation workers to remove it. Also, he is an organizer of weekly protests at the so-called “Alligator Alcatraz” in the Everglades and “Deportation Depot,” west of Jacksonville, where people suspected of being in the U.S. illegally are being housed, most without being charged with a crime.

Boggan is aware of Oliver’s activism and says it “goes directly to the heart of what it means to be Methodist in its purest form.”

“Nonviolent protests against unfair, oppressive systems and finding ways to make space for everyone to live their lives as fully as they can is what John Wesley and those early Methodists did,” Boggan said. “I look forward to Rev. Andy and other United Methodist congregations doing this type of ministry outside the walls so that we can show our current world what being Methodist really means.”

Read related story, Pastors push back in Florida

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, to the free Digests.