The Rev. Kimberly Lewis-Davis wears a police uniform more often than a pastor’s robes. The Rev. Barry Sharp was ordained by the church, but he works for the state.

The Rev. Bruce Maxwell has served the same appointment nearly 25 years, pastoring a mostly itinerant flock.

Sharp, Lewis-Davis and Maxwell are among the church’s 1,927 deacons, about 6 percent of its ordained U.S. clergy. While elders are called to lead congregations in ministry and mission, deacons are called to connect baptized Christians with their ministries in the world.

Twenty years after the 1996 General Conference established the Order of Deacons, 44 percent of deacons report that their primary appointment is beyond the local church: They serve as teachers, lawyers, writers, church-growth consultants, nonprofit agency staff or any number of other professions. That’s a big change from 2000, when research showed 70 percent had their primary appointment to a church.

“It’s an endless list,” said Rev. Victoria Rebeck, a deacon who serves as director of deacon ministry development and certification programs for the United Methodist Board of Higher Education and Ministry. “I am sure there are things I haven’t even thought of.”

That diversity of service illustrates the deacon’s call to bring the church to the world — and the world to the church.

Know Your Ordained Orders

-

Elders are ordained to a ministry of word, sacrament, order and service. They preach and teach God’s word, provide pastoral care, administer sacraments of baptism and communion, and order the life of the church.

-

Deacons are ordained to a ministry of word, service, compassion and justice. Like elders they preach and teach and provide pastoral care, but they do not administer sacraments. They are called to a ministry that brings the church into the world — and the world into the church.

A nontraditional call

Maxwell earned his Master of Divinity degree, but did not feel “called to a traditional parish.” After a couple years’ discernment, in 1992 he became chaplain at the Trucker Traveler Ministry in Breezewood, Pennsylvania.

“It became clear what God had been preparing me for,” he said.

He was in the first class of deacons ordained by the Upper New York Conference in 1997.

As “a chaplain out on the tarmac,” he ministers to cross-country truck drivers, people traveling on business or families on vacation. Sometimes he counsels regular visitors — perhaps a trucker who stops at the plaza a couple times a week — but often he’s helping people who end up at the highway stop in need of food, medical attention, car repairs or fuel.

“Sometimes it’s truly a one-shot deal,” he said. “I’ll have a 15-minute window of opportunity to plant the Gospel.”

People once were ordained as deacons as a stepping-stone to ordination as elder, but that ended in 1996 with the establishment of the two orders of clergy with distinct, but complementary, responsibilities.

The new order actually reclaimed the order of deacon described in the New Testament, one of a caring minister who trains new Christians in ministry and helps the poor and downtrodden, Rebeck said.

“You hear a lot of deacons talk about how they’re called to be a bridge,” she said.

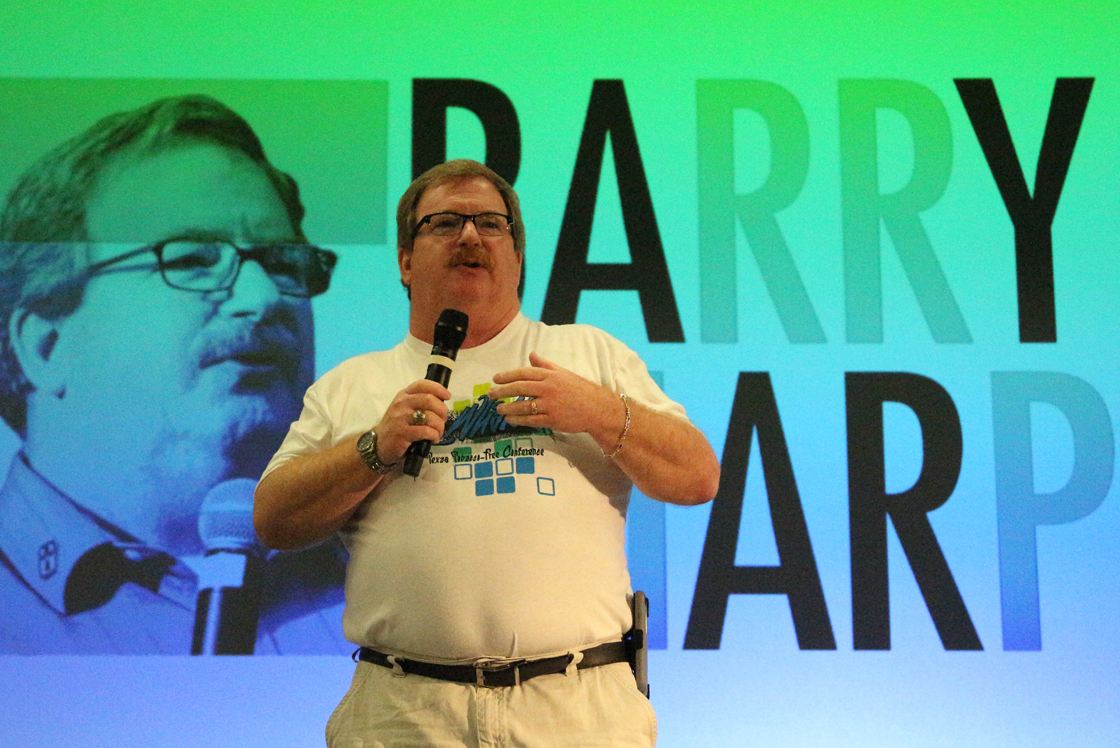

The Rev. Barry Sharp, manager of the Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch in Texas, speaks at a recent SayWhat! (Students, Adults and Youth Working Hard Against Tobacco) youth conference. Photo courtesy of Sharp

Combining ministry with other work

The Rev. Barry Sharp, manager of the Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch of the Texas Department of State Health Services, wanted to combine ministry with his work promoting physical and mental health when he was ordained deacon in the Rio Texas Conference in 2016.

Sharp, who worked in health education for 23 years, was involved in health ministry at his local church, Bethany United Methodist Church in Austin, Texas.

His ministry includes offering health programs to faith communities, arranging smoking cessation programs in churches and speaking to youth groups. He has started regular devotions at the office for anyone who wants to participate, and “my coworkers know that if they need to talk to somebody there’s somebody down the hall.”

At Bethany, he helps with music and liturgy and occasionally preaches. He and his wife lead a marriage ministry.

“We’ve got a good church staff that understands deacons and supports us,” he said.

The Rev. Joy Melton also was in the first class of ordained deacons (in the North Georgia Conference). Unlike Maxwell, she had long planned to combine her interests in Christian education and the law.

“I always knew I wanted to do both,” said Melton, a partner in the law firm of Hindson & Melton in Atlanta.

After earning a Christian education degree, she became a diaconal minister. That was a term the denomination previously used to describe people who were not ordained clergy but were certified to hold ministerial roles at local churches such as music leadership, Christian education or life-stage ministries. Melton also earned a law degree, following her father into that profession.

In the early 1990s, Melton served on a task force that wrote the first sexual ethics guidelines for The United Methodist Church. In 1996, she wrote the Safe Sanctuaries policies; she is now the author of six books on that topic. She also serves on the denomination’s Interagency Sexual Ethics Task Force.

Melton estimates she spends about half of her time as a lawyer working on clergy sexual ethics issues and the rest on more routine legal matters with families, but she is always a counselor.

“Ministers are involved with families at the time of greatest crisis and greatest joy — and so are lawyers,” she said.

Deacons not itinerant

While elders are guaranteed appointments but must serve wherever the bishop appoints them, deacons are not itinerant. The bishop appoints them to their position, but they often seek out a job on their own that helps them fulfil their ordination vows.

Those appointed outside the walls of a church usually receive a secondary appointment to a local congregation where they take missionary responsibility for leading Christians into service.

For the Rev. Kimberly Lewis-Davis, that secondary appointment is in Maple Park United Methodist Church in Chicago, where her mother, father and grandmother all were in leadership roles. She grew up visiting church members with her grandmother, and as a young adult taught Sunday school.

“Church and ministry was such a big part of my life,” she said.

Her primary appointment as a Chicago Police Department chaplain took a more winding road. After working in public relations, she joined the police department as a beat officer and plainclothes officer before getting into administration.

She began seminary classes part time while working full time at the police department, being married to another officer and caring for a 2-year-old daughter and newborn son.

“It was one of the most challenging periods of my life, but God was in the middle,” Davis said.

During a seminary internship at a hospital chaplain, she decided chaplaincy was her calling and found her niche in the police department chaplaincy office.

Now she counsels officers and their families, prays with them, visits then in hospitals, performs weddings, leads worship services and a marriage ministry — much of what “a pastor would do to minister to a flock.”

The Rev. Delana Taylor McNac, a deacon and veterinarian, founded a “Pet Peace of Mind” program to help hospice patients make plans for their animals’ continuing care. Photo courtesy of McNac

Ministry to pet owners

The Rev. Delana Taylor McNac also took a winding road, starting out as a veterinarian in private practice, then becoming a board-certified veterinary pathologist. She decided to go to seminary so she could provide Christian-based grief counseling for pet owners; later she decided to work in chaplaincy and sought ordination as deacon.

Appointed chaplain of a Tulsa, Oklahoma, hospice, she found many people concerned about what would happen to their beloved pets when they died. She started a “Pet Peace of Mind” program to help hospice patients make plans for their animals’ continuing care. In 2010, she began working with the Banfield Charitable Trust to set up Pet Peace of Mind programs in hospices across the country.

Now she runs a pet daycare and boarding facility named Dogville, where she emphasizes getting to know the dogs and the people who love them. Dogville holds memorial services for pets, police dogs, or even zoo animals and is involved with rescue work, particularly helping senior or disabled pets.

At Haikey Chapel Indian United Methodist Church, McNac and the pastor have held pet blessing ceremonies. McNac visits with church members concerned about their animals. At both appointments, she counsels people considering their pet’s end-of-life options and finds many have questions about the afterlife or intense grief over the loss.

“Being a deacon really fit my idea of how to minister to people and their pets, which for many are the reflection of God’s unconditional love,” she said.

The most recent data shows the denomination now has 29,098 ordained elders in the U.S. and 1,927 deacons (including provisional and retired clergy), said Mark McCormack, director of research and evaluation for the Board of Higher Education and Ministry. The vast majority (1,422) of deacons are female.

Rebeck of Higher Education and Ministry is excited that a growing number of deacons serve beyond the local church.

“I honestly think it’s great because it means the church is getting outside its walls,” she said. “Deacons are really a crucial part of church vitality.”

Keaton is a freelance writer in Chicago. Media contact: Vicki Brown, newsdesk@umcom.org or 615-742-5472.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.