John Wesley was onboard a ship bound for the Georgia colony in early 1736 when a ferocious storm shredded the main sail and flooded the decks.

Many of the English passengers aboard screamed in terror that they would soon be swallowed by the deep. But a group of Moravian missionaries from Germany calmly sang throughout the squall. They were unafraid of death, an astounded John Wesley later recounted in his journal.

That journey marked Wesley’s first significant encounter with a small Protestant movement that would have an enormous influence on his ministry and the Methodist movement he started.

Two years later, a disheartened Wesley was back in England wrestling with his Christian faith after a miserable time in Georgia. On May 24, 1738, friends prevailed upon him to attend a Moravian society meeting on Aldersgate Street in London.

Many United Methodists can recite what happened next. That night, upon hearing Martin Luther’s preface to Romans, Wesley wrote, “I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ alone for salvation.” Wesley’s spiritual awakening was a turning point in his life, and arguably it might not have happened without the Moravians.

Seeking Full Communion

General Conference, The United Methodist Church’s top lawmaking body, in 2016 will have a chance to recognize the denomination’s historic ties as well as potential future collaboration with Moravians.

The United Methodist Council of Bishops is asking General Conference delegates to support full communion with the Northern and Southern provinces of the Moravian Church in North America.

Full communion means each church acknowledges the other as partner in the Christian faith, recognizes the validity of each other’s baptism and Eucharist and commits to work together in ministry. Such an agreement also means Moravians and United Methodists can share clergy.

The provinces will vote on the question of full communion in 2018.

European United Methodists, starting in Germany, have already signed similar agreements with the European Province of the Moravian Church.

In some ways, such agreements make official the connection that already exists among United Methodists and Moravians.

“We concluded we have never been out of communion,” said Glen Alton Messer II, associate ecumenical staff officer with the United Methodist Office on Christian Unity and Interreligious Relationships. He was part of the church’s dialogue with Moravians.

“Wesley and Zinzendorf had their differences, but ... we never said, ‘We are not Christian brothers and sisters.’ We never rejected each other.”

The worldwide Moravian Church, formally known as the Unity or Unitas Fratrum, consists of a federation of more than 20 semi-autonomous provinces. Altogether, there are more than 1 million Moravians worldwide. More than half live in Tanzania.

So who are the Moravians? Immediately following the Council of Bishops meeting, 17 United Methodists made a pilgrimage to the denomination’s historic home base in Herrnhut, Germany, to better understand the Wesleyan-Moravian connection.

“Most United Methodists know very little about this,” said Atlanta Area Bishop B. Michael Watson, who first suggested the visit. Watson will be the Council of Bishops ecumenical officer, starting September 2016.

In addition to Watson, the group included bishops from Germany, Zimbabwe and the Philippines, as well as the United States. Also on hand were four staff members from the bishops’ Office of Christian Unity and Interreligious Religious Relationships, the denomination’s ecumenical arm.

The Moravians’ origins

The story of the Moravians begins more than 300 years before John Wesley’s day with would-be church reformer Jan Hus.

Hus was a Catholic priest in what is now the Czech Republic. Moravia, incidentally, was a Czech region.

Hus took the then-radical step of offering the cup of Communion to laity. At the time, clergy only distributed the bread and reserved the wine for themselves. Like Luther would a century later, Hus also challenged the sale of indulgences. He further asserted the centrality of the Bible over church tradition and hierarchy.

None of these activities endeared him to his leaders. At the Council of Constance in July 1415, Hus was stripped naked and burned at the stake for heresy.

Yet his followers survived and managed to repel multiple papal crusades. They called themselves Unitas Fratrum, meaning the Unity of Brethren. But after the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) when Czech lands were re-Catholicized, persecution grew and they were forced to keep their faith hidden or to flee altogether.

In the early 18th century, some families from the Moravia region approached Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf about taking refuge in his domain in Saxony. The count, a devout Lutheran, did more than give the families asylum.

He gave the Moravians a community to call their own, Herrnhut, which means “the Lord’s watchful care.”

Also, just as Wesley did in England, Zinzendorf led a movement of spiritual revival.

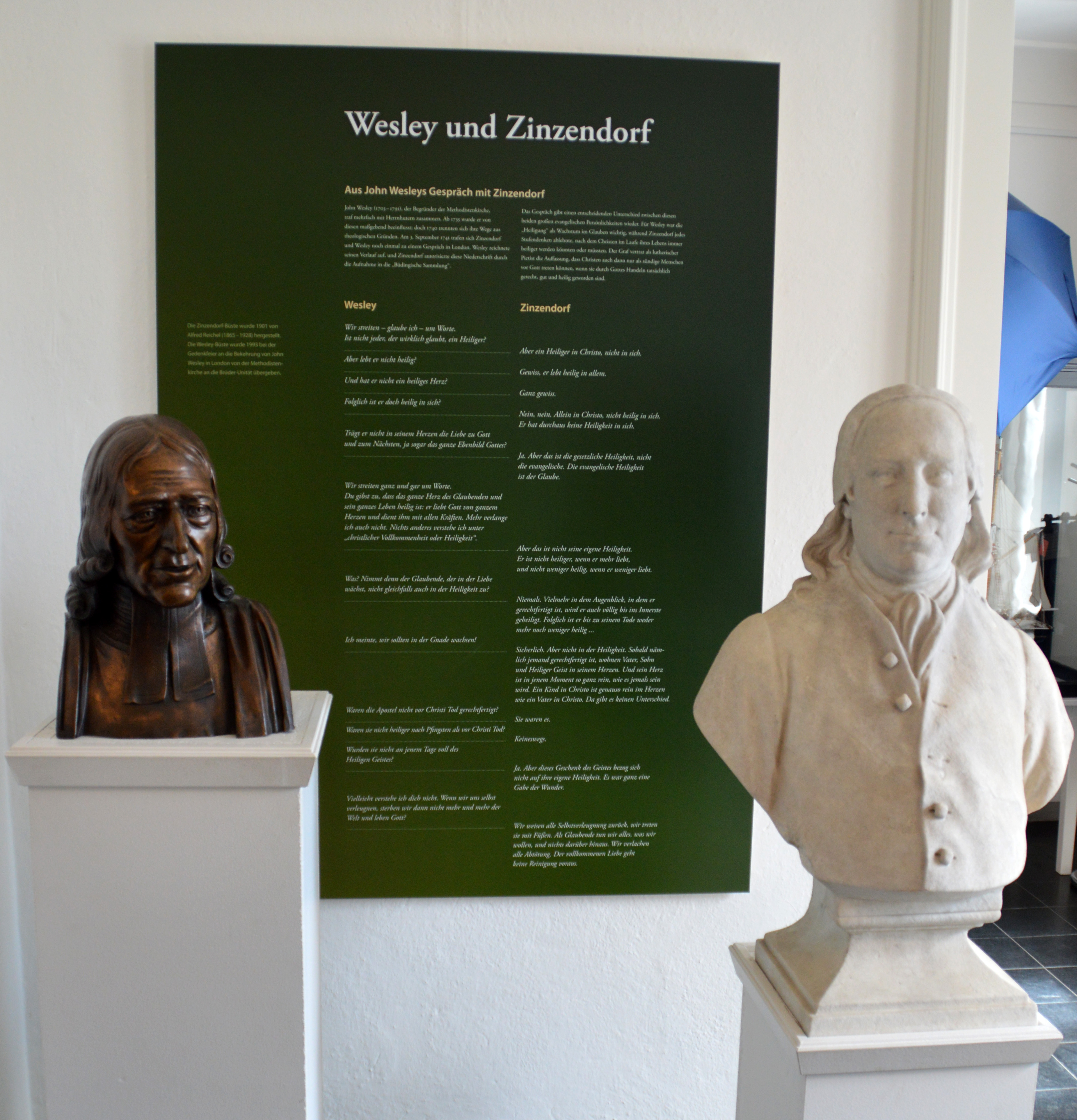

Busts of John Wesley, at left, and Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf stand side-by-side in a museum at the Moravian Congregation at Herrnhut, Germany. Photo by Klaus Ulrich Ruof

Zinzendorf and Wesley

“Zinzendorf, in my opinion, was an amazing sociologist before sociology was invented,” Jill Vogt told the visiting United Methodists. She and her husband, Peter, are pastors of the Moravian Congregation at Herrnhut.

Zinzendorf’s big innovation, she said, was to form banden, or bands: small, voluntary groups that encouraged mutual accountability and spiritual growth.

“What he recognized was that people in the different stages of their lives have connections,” Jill Vogt said. The Moravian bands were based on age, gender and marital status.

If that practice sounds familiar, that’s because Wesley learned about the bands from his Moravian friends in England and soon adapted the small groups into a key part of his own ministry.

Wesley corresponded with Zinzendorf, and the two met face-to-face in Germany and England. They used Latin, since that was a language they both knew well.

Rüdiger Kröger, director of the Moravian Church’s archives, allowed the United Methodist visitors to hold some of these letters. Wesley’s penmanship, he noted, was better than Zinzendorf’s.

Both the movements of Wesley and Zinzendorf shared much in common. They both, at least initially, were communities that operated within their respective state churches — the Methodists within the Church of England, and the Moravians within Saxony’s Lutheran Church.

Like the early Methodists, the Moravians also de-emphasized distinctions of wealth and class, and stressed human equality before God. Even today, Moravians still call each other brother and sister in casual conversation.

Both movements also gave women greater freedom to speak publicly about their faith.

But ultimately, Wesley and Zinzendorf had a falling out. A big dispute centered on differing ideas of sanctification.

“Wesley saw sanctification as a process of growth,” said Glen Alton Messer II, a church historian and ecumenical staff officer with the United Methodist Office on Christian Unity and Interreligious Relationships.

“For Zinzendorf, it’s very important to understand all holiness belongs to Christ. For Wesley, all holiness is made possible by Christ.”

Put another way, Zinzendorf saw Christ as the sole author of sanctification while Wesley saw sanctification as the result of Christ and humans working in partnership.

It’s a subtle distinction, and even Wesley told Zinzendorf he thought they were just arguing about words. But the difference was enough to prevent the merger of the two movements into one.

Still, Moravians continue to celebrate the connection between the two men. On the second floor of the Moravian church in Herrnhut is a small museum. There, busts of Zinzendorf and Wesley are displayed side by side.

Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.