Methodism’s founder wanted to minister with Native Americans and abolish slavery.

But decades after John Wesley’s death, a Methodist bishop was a slaveholder and a Methodist clergyman was responsible for one of the worst massacres of Native Americans in U.S. history.

So what went wrong?

United Methodist historians and other leaders led a livestreamed denominational town hall July 1 to explore their church’s complicated and sometimes suppressed record on race.

Their aim: To help United Methodists turn away from past transgressions and join the denomination’s renewed push against the sin of racism.

“A historical perspective gives us a glimpse into how the church chose to respond at critical inflection points in our history,” Erin Hawkins, the town hall’s moderator, told UM News ahead of the gathering.

“I think it’s important to look at the times when we have risen to the challenge and when we have fallen very short.”

Hawkins is the top executive of the United Methodist Commission on Religion and Race, which in this time of COVID-19 helped organize the virtual town hall across five locations. Other organizers include the Council of Bishops, the Board of Church and Society, the Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Women and other United Methodist agencies.

The virtual town hall is part of the denomination’s anti-racism efforts spurred by the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other African Americans at police officers’ hands.

Church leaders deliberately timed the town hall just ahead of the Fourth of July — when Americans celebrate their nation’s birth and the bold statements of equality in the Declaration of Independence.

“What does it mean to sing about the ‘land of the free’ when we still hear the jarring echoes of George Floyd calling for his mama?” said the Rev. Gary Henderson, a United Methodist Communications executive, in opening the event. “How can we celebrate ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,’ when Breonna Taylor lives no longer?”

The panelists all acknowledged that The United Methodist Church — like the nation where it was first established — has a tangled history on race.

“While Black people were attracted to and proud of the staunchly bold Methodist stance against slavery at the beginning, they were too soon to experience pain and to weep at its compromise and complicity,” said the Rev. William Bobby McClain, one of the panelists.

He is professor emeritus of preaching and worship at United Methodist Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington. He is also one of the founders of Black Methodists for Church Renewal, which has worked for Black equality.

McClain pointed out that African Americans have been leaders in Methodism since its earliest days. Preachers like “Black Harry” Hosier helped spread the movement’s plain gospel of grace across the young United States.

But even in those early days, white supremacy left its stain.

Hosier had to sleep in the carriage or barn while his white companions could sleep in the house, said the Rev. Alfred T. Day III, the top executive of the denomination’s Commission on Archives and History.

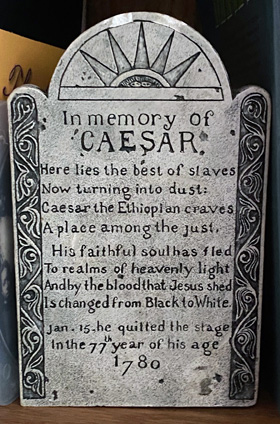

In the northern U.S., just as in the South, Day noted, the assumption was white was superior. He read from a 1780 grave marker from Attleboro, Massachusetts, that proclaimed a deceased slave named Caesar will be “changed from Black to White” in heaven.

Day listed other examples of discrimination including the 1939 formation of the Central Jurisdiction, which made segregation official church policy and remained on the books until 1968.

To view the image larger, click here.

“There is pride and shame in our history,” Day said. “Methodists can take great pride in their uniquely egalitarian message of God’s love to be experienced by all, and this ‘Love divine, all loves excelling’ is supposed to be impartial.”

But, he said, the shame is that too many whites did not live up to the core theology that first drew African Americans and Native Americans to Methodism.

The Rev. Lisa Dellinger, a scholar and pastor in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference, specifically addressed how Christians used their theology to justify displacing and even slaughtering indigenous people.

She said the common description of the Americas as a “New Jerusalem,” led many settlers to see indigenous people as subject to conquest like the Canaanites of the Old Testament.

From the 1860s to the 1960s, Christian missionaries systematically separated as many as 100,000 Native American children from their families and sent them far from home to government- or church-run boarding schools. At these schools — some of which were Methodist — youngsters were punished for speaking their native language, stripped of their belongings and in some cases, abused.

“Native peoples are complex,” said Dellinger, who is Chickasaw and Mexican American.

“But what has been a unifying experience for Native people, and not necessarily a positive one, has been this sense of displacement — the sense of being a stranger in a strange land, and this land is your home.”

In addition to examining past sins, the panelists answered questions from viewers about ways to chart a better future.

Dellinger and McClain cautioned predominantly white churches about thinking it is the job of people of color to desegregate congregations.

“My biggest concern when we talk about integration is: Who is being asked to do the work?” Dellinger said. “Who is being asked to show up where the primary focus is to alleviate white guilt?”

Alison Collis Greene, a professor of American religious history at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, described what an anti-racist church looks like.

“If you are talking about a predominantly white anti-racist church, that church makes real space for non-white voices,” Greene said.

She added that white churchgoers also need to speak to fellow whites about eliminating racism — especially those “who don’t want to talk about the past because they don’t want to talk about the parts that are hard for them.”

The town hall is the most recent step in the denomination’s initiative, Dismantling Racism: Pressing on to Freedom.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

The Council of Bishops launched the initiative on Juneteenth — the June 19 celebration of the end of U.S. slavery. Less than a week later, bishops and other United Methodists followed with an unflinching “Service of Lament, Repentance, Communion and Commitment.”

While the town hall’s focus was on U.S. experiences, Hawkins said, the hope is for churches across the multinational denomination to commit to combat racism and prejudice in their own context.

The Commission on Religion and Race hopes to next have a town hall about activism across generations. Agencies, Hawkins said, will continue to provide resources and organize general events to help people across the denomination engage in justice advocacy.

“I would really like to see this effort that’s been turned on at the general level to move closer to the local level,” she told UM News, “because that is where the important change happens.”

McClain said that individual and systemic racism remain problems churches need to tackle.

“Until we dismantle and destroy the pillars that prop it up,” he said, “we shall be on the pain side of history rather than the pride side.”

Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.