Editor’s note: This is the second in an ongoing series about churches in West Virginia dealing with the opioid crisis.

There was about to be a big fight, and it was all the Rev. Barry Steiner Ball’s fault.

The pastor and retired Drug Enforcement Administration agent had come to Spruce Street United Methodist Church in Morgantown to present his “What If?” initiative, a West Virginia Conference ministry encouraging churches to confront the opioid epidemic. Church members were at one table and police at another. A woman he didn’t know was sitting at a third.

When Steiner Ball asked if anyone had seen hypodermic needles in the church parking lot, Caitlin Sussman stood, identified herself as a social worker from Health Right — the needle exchange across the street — and said to call her any time there were needles to clean up.

“I thought, there are police over here and no telling how the church members felt about it,” Steiner Ball said. He braced for conflict.

That’s when a police officer said, “That exchange is the greatest thing to happen in this town.”

Turns out Sussman already had buy-in from the local police, and that meeting sparked a partnership with the church as well.

“We were moved by the presentation and asked ourselves what we could do, so we approached Caitlin,” said Spruce Street member John Beaumont.

“The commitment of the church made me feel inspired and secure. I was really grateful,” Sussman said.

Now, a group from the church goes over to Health Right once a month to spend time with clients of the harm reduction program coming in for clean needles. They bring snacks, board games, materials to make crafts and a hope to spark conversation.

Bob Jones, a former Spruce Street member who participates in the outreach, said the church has always been mission-oriented but tended to make donations more than personal connections.

“Something happened that caused folks from this community to take a risk and get to know folks in that community 50 yards away from us,” he said.

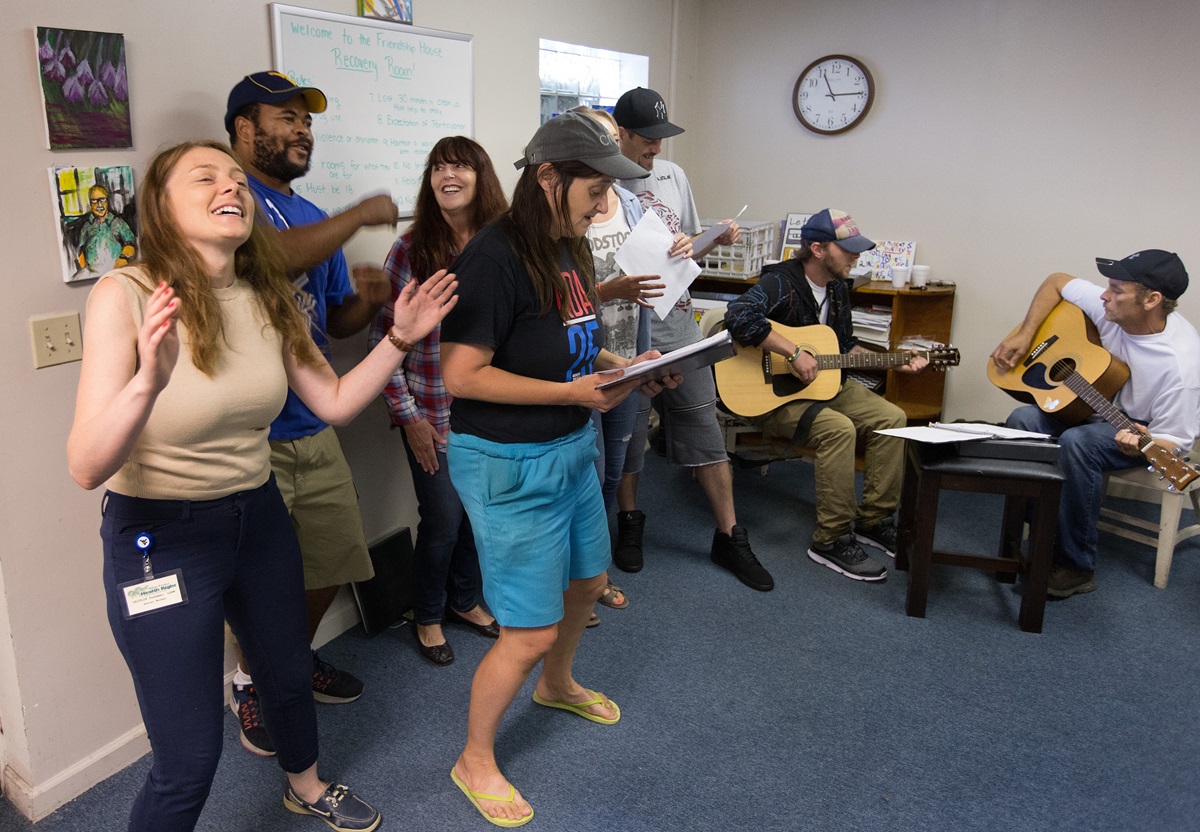

Church members also visit with participants in other Health Right programs. In addition to the needle exchange, Health Right runs a day center for people dealing with homelessness, mental illness or substance abuse. The center, Friendship House, offers programs like art and music therapy for patients, and has a choir that performs publicly. Jones has even joined the choir.

Sussman describes the partnership as “beyond what I would’ve imagined.”

It can be daunting for churches to minister directly to those with such different circumstances than their own, but that ministry is vital and rewarding.

“There’s a disconnect between a lot of broken people and the church,” said the Rev. Ross Thornton, who runs a street ministry in addition to pastoring Fourth Avenue United Methodist in Huntington.

The homeless and the addicted see church as a place to get a meal but may not expect anyone to actually care about them, so Thornton considers it necessary to go to them instead.

“We’re not making any difference if we’re only hanging out inside the walls. John Wesley preached on the streets, too.”

Huntington has experienced some of the highest rates of opioid addiction in the state, if not the nation. In 2016, the city suffered 28 overdoses in a single day and is the setting for the Netflix documentary “Heroin(e).”

How to get involved

Even the Rev. Barry Steiner Ball, whose ministry is to change opinions about addiction, needed some eye-opening.

“A year and a half ago, I would’ve said to close those needle exchanges and stop enabling people,” he said, but seeing the openness of the police and the church toward Health Right “transformed my ministry.”

Now, he volunteers as a chaplain at a needle exchange in Huntington.

Other observations from those in the West Virginia Conference:

• Celebrating a Day of Hope is a way to raise the issue of addiction at church. A counselor or someone in recovery can share that experience with the congregation.

• Distributing information on social services and recovery meetings can help direct people to the help they need.

• Building relationships may be the best thing a church or anyone can do to help people struggling with addiction.

• Providing community meals and help with clothing or personal items can also create moments for devotionals or prayer support.

• Offering a church presence in drug courts is helpful and there are opportunities for church involvement through every step of the process.

• Partnering with recovery homes can assist residents with needs such as providing transportation to medical or legal appointments.

Thornton said he tries to get folks off the street and into recovery, but also offers to pray with them and just remind them they are loved. Not everyone is receptive — he’s been ignored and even threatened with violence. He also has a number of people show up at Fourth Avenue “because they know our church is a place they will be welcomed.”

Donnie Smitley met Thornton through his street ministry and now comes to his church. A former crack addict, he said, “It’s only by the grace of God I’m here.”

Welcoming is important to the Rev. Mike Smith as well. Smith pastors Nighbert United Methodist in Logan, another area hit hard by opioid addiction. The church is next door to a clinic that administers suboxone, a medication used to treat dependence.

Smith routinely hits the streets and gets to know the community, which helps build trust with those who are often suspicious of the church.

“There’s a sacrificial aspect to it, committing your life to changing other people’s lives,” he said. “If you’re willing to really get involved, it’s intense.”

The Revs. Harold and Cheryl George and Deb Dague take that intense way of changing lives to another level. In addition to ministering to congregations, they are also EMTs.

Harold George said he focuses on the job at hand but never really takes off his clerical collar.

“You pray on the way to calls, you pray your way through calls, you pray for the people after the calls.”

He also has to pray for other first responders. The rise of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid many times more potent than morphine, has put emergency personnel at risk, as even physical contact with the drug could prove fatal. Crews carry extra Narcan, a drug that can “revive” overdoses, in case they succumb to fentanyl exposure.

Dague works with Brooke County EMS in Wellsburg. “People say you can’t be an EMT and serve a clergy role, but this is someone’s worst day and you’re with them to give care and hope,” she said. “That’s how they’ll remember you. To me, it absolutely is a ministry.”

Her coworkers share her concern for those struggling with addiction.

“When we get habitual users, we try to talk to them and hope it’ll be a wake-up call. I hope they get back into rehab and make it,” said Jeff Luck, Brooke County’s paramedic supervisor.

Emergency personnel are prone to becoming cynical about the ability or willingness of addicts to change. The pastors’ beliefs in redemption and forgiveness help fight such thoughts.

“The attitude now is ‘they’re a waste, just let them go,’ but Jesus never let any of us go,” said Harold George. “I don’t know how many chances Jesus gave me before I came to him and every time you bring someone back with Narcan is another chance they can go to rehab.”

Judge Eric O’Briant knows all about second chances. And third. And fourth.

O’Briant oversees Logan County’s drug court, a specialized program that targets offenders with substance abuse problems. Rather than incarceration, drug courts walk defendants through a structured program of treatment and resources like life-skill training and housing and job assistance to help them rebuild their lives and, hopefully, stay out of the legal system.

The program takes 12-18 months to complete and graduates emerge with a high school diploma, a job, at least six months of sobriety and the tools to live independently.

A lifelong member of Nighbert United Methodist, O’Briant said his faith helps him in his job. He prays daily for the wisdom to make the best decision for each individual in his court. He said his job is much more rewarding than a traditional judge’s role.

“The easiest thing a judge can do is send someone to the penitentiary. What we’ve been doing isn’t working and we’ve got to break the cycle.”

The drug court model is proving successful. Research by the National Institute of Justice suggests they have both lower recidivism rates and lower costs than incarceration.

Smith is a regular presence at drug court. He hopes to build trust among program participants so they may accept support from Nighbert United Methodist and O’Briant values the church’s partnership. “They see him in drug court and if they come to the church for a weekly meal, they know he’s there and cares,” the judge said.

Nevada, a drug court participant who attended worship at Nighbert and helped with the meal program, was one who expressed gratitude.

“Drug court helps a lot of people and I’m proud that Judge O’Briant helped me out. He could’ve just sent me to prison,” Nevada said.

Smith later reported that Nevada did not graduate from drug court and is currently incarcerated. It’s a reality that is common for those in recovery ministry. However, the pastor lifted up a woman named Jacqulyn who just finished a recovery program and will officially join Nighbert this coming Sunday.

“It really speaks to the reality of this illness,” Smith said. “You have one person so close who fails to overcome their disease, and another who succeeds. Christ always offers hope of a new life.”

Ministering to those in addiction requires patience and open-mindedness. Addiction is powerful. Addicts lie. They may steal. Most who recover don’t do so on their first try, and some never do. Breaking the stigma of addiction is an area where the church could have great impact — but that stigma must first be confronted within the congregation.

The Rev. Jeff Allen, executive director of the West Virginia Council of Churches, said judgmental attitudes toward addiction make no sense when everyone in the state is affected in some way by opioids.

“The church doesn’t deal well with brokenness,” he said. “Someone told me, ‘I can walk into any AA meeting and know everyone understands where I am, but when I walk into a church I feel judged.’”

As a recovering addict, Ann Hammond can relate. A member of United Methodist Temple in Clarksburg, she still senses judgment from others despite being drug-free for 12 years.

“One woman said to me, ‘To some people, you’ll always be an addict.’ I was caught off guard because none of these people even knew me as an addict, and I feel so distant from the person I was. It’s hard to feel that judgment,” Hammond said.

Churches considering this ministry need to know that “change is slow and you can’t be afraid to take risks,” said Sussman, the social worker from Health Right, which partners with Spruce Street United Methodist Church.

“God will bring people your way,” said Smith, the pastor of Nighbert United Methodist, which welcomes drug court participants. “If there’s a fertile ground where people’s lives can be changed, churches need to commit themselves to those people.”

Read the first story in our series, Conference asks 'What If' the church confronted the opiod crisis.

Butler is a multimedia producer/editor and DuBose is staff photographer for United Methodist News Service. Contact them at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.