Key points:

- United Methodists in Chicago and Portland, Oregon, are striving to lead courageously as their cities face threats of militarization and an onslaught of masked federal agents.

- In both the Northern Illinois and Oregon-Idaho conferences, pastors are seeking to protect neighbors and offer comfort where they can.

- Northern Illinois has set up an emergency fund for immigrants fearful to leave their homes.

- United Methodists also want to set the record straight about what’s happening in their cities.

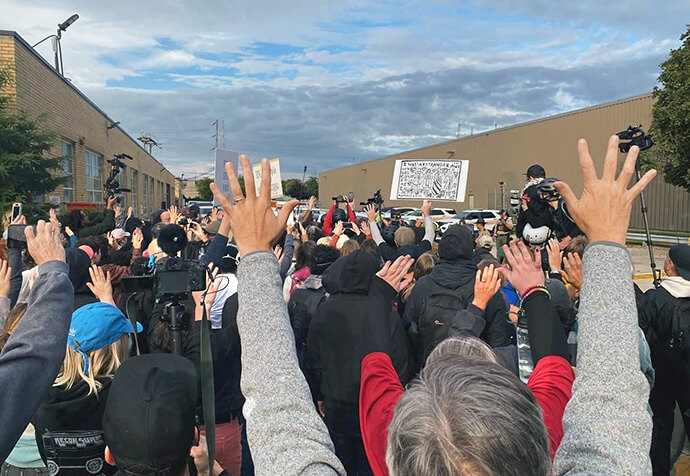

Beneath the shadow of the Broadview Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility, about 40 Chicago-area clergy set out Oct. 10 to bring the light of Christ’s presence.

But as the Rev. Abby Holcombe prepared to welcome protesters and others present that day to partake in Holy Communion, the United Methodist pastor noticed some in the crowd pointing behind her. So, she turned around.

“We’re serving communion, and they walk out with gas masks,” said Holcombe, pastor of the West campus of the United Methodist multi-site congregation Urban Village Church.

“All of a sudden, some troopers had gas masks on, and I thought, ‘What do you think I’m going to do here?’”

Just the day before, an Illinois judge blocked federal agents from using chemical irritants and other types of force to disperse crowds after agents outside the same facility repeatedly fired pepper balls at a praying Presbyterian pastor.

However, Holcombe had no idea whether the judge’s order would be followed.

As President Trump has made moves to deploy armed National Guard troops to both Chicago and Portland, Oregon, United Methodists have stepped up to protect their neighbors, comfort the distressed and bear witness to a more Christ-like way.

They are following the well-worn path trod by fellow church members in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. Both cities also have faced the Trump administration’s militarization and the accompanying onslaught of armed masked federal agents seizing suspected undocumented immigrants from the streets.

Many United Methodists see standing up for immigrants as part of following Jesus’ command to love their neighbors and, as part of living their baptismal vows, to “resist evil, injustice and oppression.” Confronted with the cold calculations of ICE, these churchgoers — sometimes at personal risk — are bringing the warmth of their faith.

“These deployments are acts of intimidation meant to instill fear. No one is safe from such tyranny, and no one is alone in facing it,” said Bishop Cedrick Bridgeforth, who leads the Oregon-Idaho, Pacific Northwest and Alaska conferences.

“We will continue to work with our ecumenical and interfaith partners. We will not abandon those in need. We will show up, listen to those who have been silenced, and use our facilities to support partners doing work we cannot do alone.”

The Northern Illinois Conference has established an Emergency Solidarity Fund to provide food and other essentials for immigrants now fearful of leaving their homes.

“You can imagine that winter brings economic challenges to many, but in this moment, immigrant communities in particular are suffering,” said Bishop Dan Schwerin in a statement. He leads the Northern Illinois and Wisconsin conferences.

While federal judges so far have blocked the full deployment of National Guard troops in Chicago and Portland, United Methodists in both cities say the greatest threats to peace have come from ICE and other federal agents.

What’s happening in Chicago

Before Oct. 10, Holcombe of Urban Village had already experienced agents’ violence. At an earlier nonviolent demonstration at the Broadview facility, she said agents shot her with rubber bullets.

“I told them they might not have to answer to me for this one day, but they will have to answer to God for what they’re doing — and that they need to put their weapons down immediately,” she said.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

Instead, she said, the agents shot her. “I wasn’t even trespassing,” she added.

Fortunately, the Oct. 10 communion service went far more peacefully. No one deployed any tear gas, and she said more than 120 people came forward for the sacrament or a blessing.

After the demonstration, Holcombe and three other clergy approached an Illinois State Police officer standing watch outside to ask if they could bring communion to the people detained in the facility. The officer told the pastors that he would ask ICE if they could. He then had to relay that ICE had denied the request. A coalition led by Catholic priests faced the same denial the following day.

Through a spokesperson, the Illinois State Police told United Methodist News that it does not have any authority over detainees or the operation of the ICE facility in Broadview.

“Our mission, along with other local law enforcement agencies, is to ensure the safe expression of First Amendment rights and protect the safety, property and access to everyone in the community.”

The Rev. Hannah Kardon, who was among the clergy who sought to bring the Eucharist to the people detained, has continued to join in nonviolent demonstrations at the Broadview facility. Baptist News Global reported that the state police aggressively arrested the United Methodist pastor along with eight others on the morning of Oct. 17 as they stood peacefully in the street shouting “Who do you serve? Who do you protect?”

Kardon is the pastor of the United Church of Rogers Park, a United Methodist congregation in a multi-ethnic North Side Chicago neighborhood that has been particularly hard hit by the ICE crackdown.

She told United Methodists News on Oct. 13 that the same day she was refused access to bring communion, ICE also turned away Illinois’ U.S. Senators Dick Durbin and Tammy Duckworth from the Broadview facility.

“They are willing to tear-gas us, shoot us with pepper balls, beat us and prevent us from access to the facility,” Kardon said. “If they’re willing to do that to clergy and elected officials in public, what are they doing to the people inside?”

What is happening outside the facility is appalling on its own, Kardon and other clergy said.

Kardon described what ICE is doing as “kidnapping” as masked agents with no warrants drag mostly brown and Black people away in unmarked cars.

“The only thing I have had to be afraid of in my community is ICE,” she said. “Chicago is a place that is full of love and care. Neighbors rely on one another. This is an extraordinary city that felt so normal until the Department of Homeland Security came.”

Since the U.S. department launched what it’s calling Operation Midway Blitz on Sept. 8, the department estimates its agents have arrested more than 1,500 people as part of immigration enforcement in Illinois and surrounding states.

The operation already has taken one man’s life. On Sept. 12, ICE agents shot and killed Silverio Villegas Gonzalez, who had just dropped off his kids at school and daycare, in a traffic stop. Video footage disputes ICE’s claim that the shooting was in self-defense. The Movement in the City/Franklin Park United Methodist Church, located just a few blocks away, held a memorial service for Gonzalez.

The most dramatic of the raids took place predawn Sept. 30, when hundreds of federal agents from multiple agencies stormed an apartment building, pulled adults and children from their beds and questioned nearly everyone inside as a Black Hawk helicopter circled the building. The operation led to 37 arrests— most of whom the department alleges have criminal histories.

Homeland Security asserts it is targeting the worst criminals. But an investigation by the Chicago station NBC 5 found no arrest records or criminal histories for 18 of the 22 people the department labeled “the worst of the worst.”

As of Sept. 21, the data-collection website TRAC said, 71.5% of the nearly 60,000 people in ICE detention nationwide had no criminal conviction. Merely being in the U.S. without documentation is not a crime but a civil offense. A ProPublica investigation also found ICE has detained more than 170 U.S. citizens since Trump’s second term began.

Throughout the Chicago area, United Methodists and others have taken to carrying whistles to sound warnings whenever ICE agents are nearby. Chicago-area residents also are using various text systems to alert each other. People are bringing groceries to immigrant neighbors, keeping an eye for ICE outside houses of worship and walking kids to school so their parents aren’t in danger.

“These are people you would run into in your everyday life who are doing extraordinary things,” Kardon said, “because they see what’s happening to our neighbors.”

Ways to help

The Northern Illinois Conference has set up an Emergency Solidarity Fund for immigrants afraid to leave their homes amid the onslaught of masked federal agents grabbing people from the streets.

People served by United Methodist ministries or living in churches’ neighborhoods may request help from this fund. Clergy also can recommend support for needs they know about.

A small group that includes clergy, lay people and conference staff will review the requests.

Clergy in the Greater Northwest Area, which encompasses the Oregon-Idaho, Pacific Northwest and Alaska conferences, have put together a video about what’s happening. In the video (see below), pastors speak out for the United Methodist baptismal vows and against the human-rights violations they see as against those vows.

The Rev. Jen Stuart, senior pastor of First United Methodist Church in Bend, Oregon, organized the video to make sure United Methodists’ voices and values are heard.

“We keep hearing that Christians are behind what’s happening,” she said. “Well, I’ve never been part of a congregation that would support what’s going on here.”

Watch video below.

ICE has left no metro Chicago community untouched — including the relatively well-heeled suburb of Evanston, which is home to both Northwestern University and United Methodist-related Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary.

The Rev. Britt Cox, executive pastor of First United Methodist Church of Evanston, was about to lead prayers for the people during Sunday service Oct. 12 when she and other worshippers received a text alert. That morning, ICE agents had detained two men at the local Home Depot. She prayed and comforted parishioners horrified by the news. The community canceled children’s soccer games that afternoon in hopes of keeping ICE away.

“Just to think about people we know, people we love, people we worship with, people we grocery shop with being targeted with such violence just feels so anti to what our faith is about,” Cox said.

The Rev. Lindsey Joyce coordinates the Northern Illinois Conference’s rapid response. She said what’s happening in Chicago should not be seen as immigration enforcement, “but instead the federal government occupying a U.S. city.”

Nevertheless, the kindness and support she sees in the city’s diverse neighborhoods gives her hope.

“Chicago is more united than I’ve ever witnessed, and people have been organizing around immigration in Chicago for decades,” said Joyce, who also is the pastor of Grace Church Logan Square. “It really feels to me like the early days of the pandemic when we were all taking care of each other.”

What’s happening in Portland

More than 2,000 miles to the west, United Methodists and other residents similarly are acting in solidarity to protect their neighbors.

Conditions, so far, have been much worse in Chicago with ICE using more aggressive tactics and making more arrests in the nation’s third-largest city. For many in and around Portland, the most frustrating development is the disinformation being spread about their city.

While Trump has falsely described Portland as “war-ravaged” and “on fire,” a number of Oregonians have shown that the city is not only war- and fire-free but also full of whimsy. At the ICE facility outside downtown Portland, people come out dressed in inflatable costumes to resemble giant frogs, Tyrannosaurus rexes, a unicorn and even a capybara. They often dance in front of the masked ICE agents.

“They want us to be afraid so we won’t protest, so we won’t speak up. They want us to be violent, so they can justify their violence,” said the Rev. Heather Riggs, pastor of Montavilla United Methodist Church. “They don’t know what to do with weird.”

Riggs acknowledges the city has its share of challenges. Her church works to provide services and shelter for Portland’s large homeless population. However, ICE activities are not helping the situation. In fact, ICE briefly detained a volunteer with the church’s ministry as he dropped his child off at preschool. The man is married to a U.S. citizen and in the final stages of getting his green card.

United Methodist clergy in Oregon have found success in keeping ICE at bay through the ministry of accompaniment as well as mutual aid. Riggs, who works with Portland’s HereTogether ecumenical coalition, has walked with immigrants to court hearings as they complete the legal process to live in the U.S.

“We’ve made a difference,” Riggs said. “Our constant presence has meant that ICE agents and DHS agents are no longer sitting in the courtrooms waiting to snag people at the end of their case.”

The Rev. Keren Rodriguez, a United Methodist and congregational organizer with the Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice, said she sees faith leaders really listening to migrant communities and learning when they should step in.

“The faith communities I have seen thrive have been the ones that are organized in their own way and that are connected to their neighbors,” said Rodriguez, who also is a part-time pastor at Aloha United Methodist Church. “If a faith community is connected to their immigrant community members and know what their needs are, they are going to be trusted individuals.”

United Methodists throughout the Greater Northwest area also hope to counteract the sense that brutality toward immigrants is in any way compatible with Christianity. After all, Jesus in Matthew 25 commanded his followers to welcome the stranger.

The Rev. Drew Hogan, pastor of Tabor Heights United Methodist Church, has been showing up regularly at prayer vigils at the ICE facility to demonstrate Christ’s teachings.

He noted that demographers have dubbed Portland “the None Zone” because such a high percentage of its population identify their religious affiliation as "none."

“Some of the loudest Christian voices are so harmful in their theology that I wanted to be able to show up as a presence and help disrupt that narrative,” he said. “I want to be able to come alongside people and help them understand that there is a church community that wants to be there.”

Hahn is assistant news editor for UM News. Contact her at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free UM News Digest.