Editor’s note: This is the first in a four-part UM News series on legacy Black United Methodist churches that are maintaining their traditions while also doing innovative ministries to serve the present age. Every week in March, the series will feature venerable yet still vital African American churches in the United Methodist connection.

“To serve the present age, my calling to fulfill,

O may it all my pow’rs engage to do my Master’s will!”

— From “A Charge to Keep I Have” by Charles Wesley

Each year, annual conferences across The United Methodist Church gather and sing Charles Wesley’s venerable hymn “And Are We Yet Alive.” Today, many historically Black United Methodist churches in the U.S. struggle to answer that question, as they strive to overcome decades of decline in membership, money and mission — made worse by the COVID pandemic.

But while still steeped in their traditions, some are trying nonetheless to start new ministries in their old buildings — and perhaps find ways to pour new wine into old but fortified wineskins and make it work.

Mother African Zoar United Methodist Church, Philadelphia

Many of the oldest African American congregations were born of racism, when their earliest members were forced to leave biracial mother churches to find religious freedom, fairness and dignity on their own.

African Zoar United Methodist Church, whose biblical name means “a place of refuge,” is the oldest still in operation. It emerged from Historic St. George’s Church in 1794, when Black members reluctantly left because of racial bigotry and discrimination. Other Black members had already left in 1787, led by St. George’s ministers Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, to start new congregations of their own. Allen’s departure led to his founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1816.

Today, Mother African Zoar, whose maternal moniker comes from its legacy of birthing seven more churches, is still serving its urban community through worship, discipleship education, creative outreach ministries and grassroots organizing in a quest for social justice.

Celebrated in the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference for its urban ministry efforts, the 230-year-old congregation — now doing ministry in its third location — long ago served its community by offering a school and baby clinic, credit for home loans and a secret refuge for escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad.

The church collaborates with partners to address poverty, hunger, crime, medical and mental health problems and voter apathy. It also does “mobile ministry” in an equipped recreational vehicle that brings hundreds of underserved neighbors the food, clothing, health information, prayer and other assistance they need.

Mother African Zoar’s average worship attendance has grown to about 90 since its lead pastor, the Rev. William Brawner, arrived in 2021. He previously was the conference’s part-time coordinator of urban ministries and then youth and young adult ministries.

More new members are coming from the surrounding neighborhood and enthusiastically joining longtime Zoar members in ministry, said Brawner. Many say it’s because of his relatable preaching, the lively worship and the church’s credibility in the community.

Brawner accepted the conference’s 2024 Herbert E. Palmer Urban Ministry Award last year alongside members of the congregation. He said church members showed up to support “the ministry that God has laid on all of our hearts. We are thankful that we are recognized, but we’re mostly thankful that we’re able to serve our people just like Jesus would do.”

Zoar hosted a town hall-style gathering Feb. 27, titled “We Walk by Faith,” to address “rising threats to our churches and communities in a call for solidarity and action.” Over 130 attendees came to listen, learn and explore solutions to economic, housing and environmental injustice. They also heard about the current harsher enforcement of immigration laws, increasing incarceration rates and growing community trauma.

Most Black churches historically have been involved in movements for civil rights and social empowerment. But they also have been essential places of nurture for body and soul, helping to feed, clothe, educate and inspire their neighbors.

“Zoar’s legacy continues because they know who they are and whom they serve,” said the Rev. Andrew Foster III, the church’s district superintendent. “Their relevance is evident in the ways they have managed to be in ministry through both word and deed throughout the ages.”

Asbury United Methodist Church, Washington, D.C.

Asbury United Methodist Church’s founding members also left their mother church, Foundry Methodist, in 1836, due to racism. Today, Asbury is holding its ground socially and spiritually, surrounded by the city’s confluence of wealth and poverty. The church has fed its food-insecure neighbors through a weekly distribution of food, along with underwear and toiletries, and a Sunday breakfast for over 25 years — except when the pandemic temporarily closed its ministries.

When the church reopened, its weekly guests were no longer primarily older African Americans but increasingly young Hispanic families and, more recently, Asian families. The congregation’s mission changed, too, when church members decided to feed not only bodies but souls as well.

Through strategic planning and coaching, recruitment of volunteers, and the aid of a major grant plus additional funds, Asbury added a new ministry in July 2023, joining a popular movement called Dinner Church. Now, on the first Saturday evening of each month, the church welcomes diverse guests and church members to enjoy a free meal with a faith message, music, Scripture readings, Holy Communion, prayer and guided conversation. All are seated at covered dinner tables and served meals, as they converse over suggested table topics in the church’s decorated downstairs fellowship hall.

With community support, talented cooks, dedicated volunteers and vigorous promotion, the church draws about 60-plus diners, making the ministry a success, albeit with some challenges, including the need for more funding and food. More community guests — including local apartment tenants and unhoused and transient neighbors — now are attending Sunday worship and other church events. And fledgling relationships are slowly forming among some regulars, according to program coordinator Carol Travis.

Asbury reports 858 members, with an average of 105 in worship attendance onsite plus 589 more online.

“Our hope for Dinner Church is that the message ‘God loves you’ will multiply and transform our church and community through discipleship,” Travis explained.

Lead pastor the Rev. Ianther Mills, who researched the Fresh Expressions model of starting new Christian communities beyond the traditional church setting, shared her dreams for the ministry.

“I’m hoping we can go deeper and farther in our community engagement and be more invitational. I hear and can see how much it is blessing our members and guests all around.”

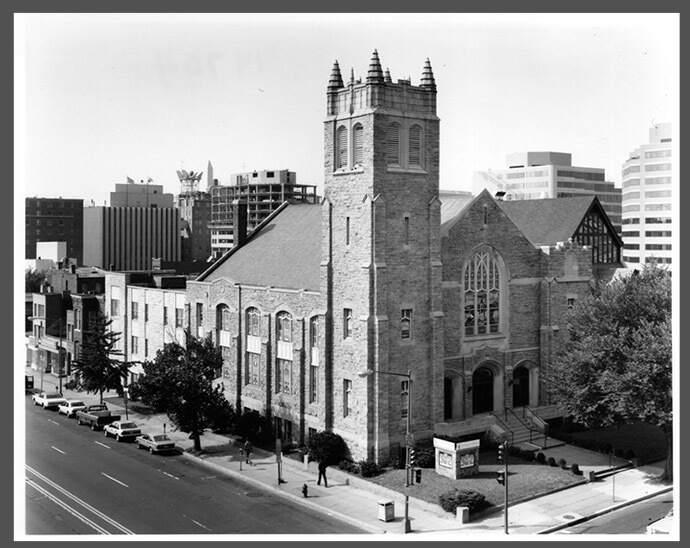

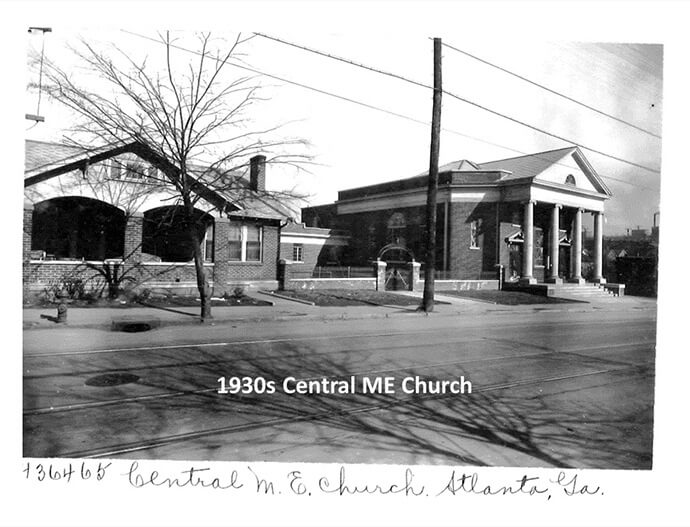

Central United Methodist Church, Atlanta

Founded as Clark Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church in 1866, a year after the Civil War, Central United Methodist Church is the birthplace of two historically Black, United Methodist-affiliated institutions of higher learning: Clark College, now Clark Atlanta University, and Gammon Theological Seminary. Today, the church hosts the university’s music education department on the second floor of its own education building.

Located on the edge of downtown Atlanta, just steps (.2 miles) from the Atlanta Falcons football stadium, Central has long seen itself as “The Church at the Heart of the City, with the City at Heart.”

Indeed, it was a force for social change activism and community outreach, especially during the 1968-1986 pastorate of the beloved Rev. Joseph Lowery. He involved the church in his civil rights work for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which he cofounded and led along with and after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

That tradition continues in its local partnerships and community services, including a food pantry that provided nearly 51,000 pounds of food to more than 1,600 families last year. It also continues in its efforts to increase voter education and participation during elections. Leading up to the November 2024 elections, when new lead pastor the Rev. Brian Tillman noticed the lack of full-time, early voting polling precincts west of downtown Atlanta, he arranged for Central to host one to ensure equality and justice.

Now the 159-year-old, intergenerational church is trying to manifest both tradition and innovation, starting with its worship life. First, it sought coaching from the Rev. Olu Brown, a popular church growth consultant who planted and led Impact United Methodist Church in East Point, Georgia, to become one of the denomination’s fastest-growing churches. Then, leaders decided in 2024 to end the single Sunday service that blended traditional and contemporary worship styles.

In January, guided by research and planning, Central began offering traditional worship at 8 a.m., still “rooted in the Black experience,” and saw an increase in attendance. In April, it plans to launch “a new, nontraditional, more upbeat, inclusive and multifaceted experience” that should draw more young and diverse worshippers from its college and community surroundings.

“We’ve been here a long time and will be here a long time because we believe in responding to the needs and aspirations of our community,” Tillman said. “And we will always be grounded in sharing God’s Word for all of His people.”

Coleman is a UM News correspondent and part-time pastor.

News media contact: Julie Dwyer, news editor, newdesk@umnews.org