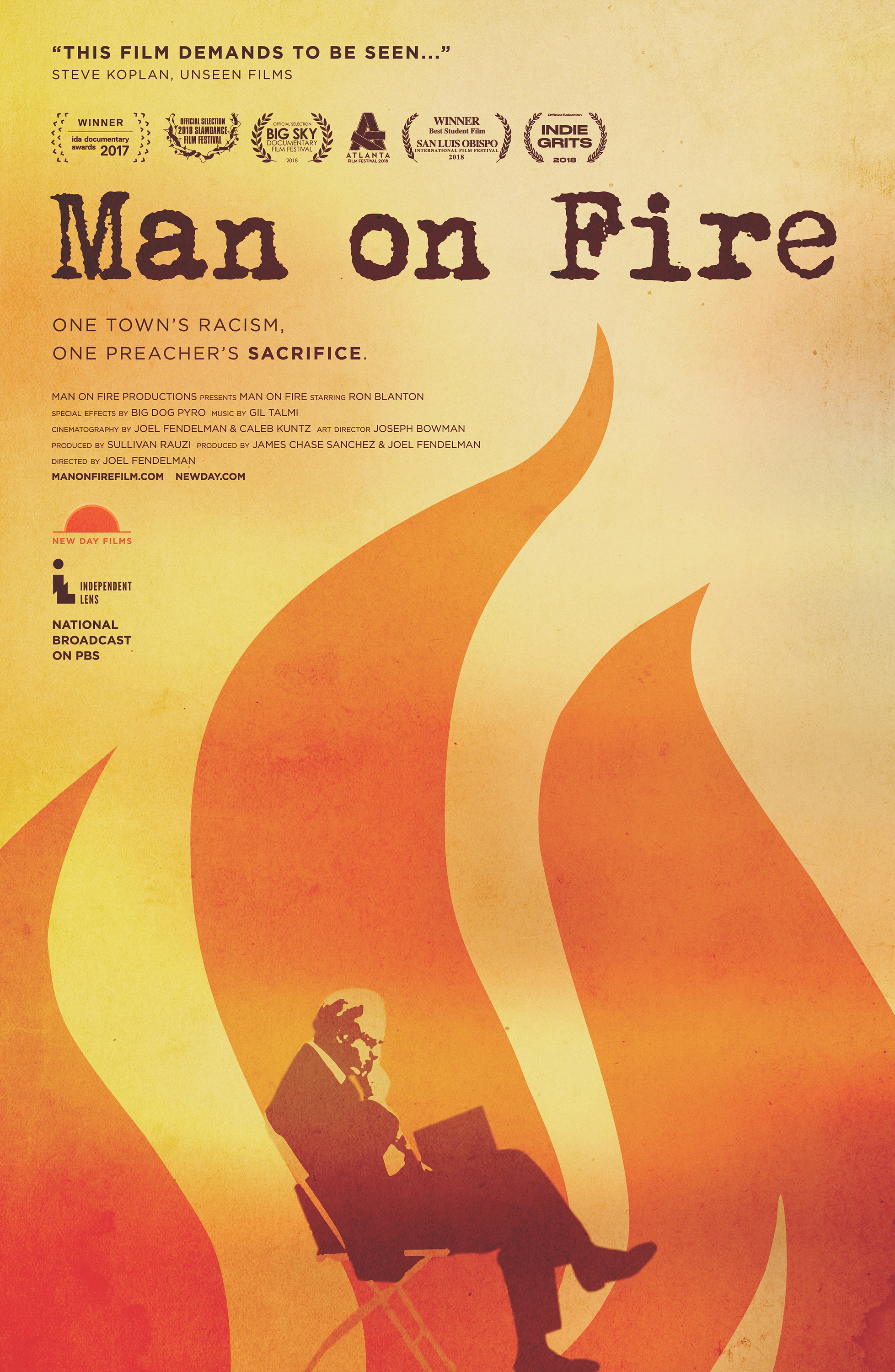

The new documentary “Man on Fire” doesn’t pretend to answer all the questions raised by a retired United Methodist pastor’s suicidal protest of racism.

But one thing the filmmakers know for sure: The Rev. Charles Moore should not be dismissed as merely crazy for setting himself on fire in his hometown of Grand Saline, Texas.

“Ultimately, to view Charles through a lens of like, ʽHe’s mentally ill’ — that’s a copout, that’s a way of saying we don’t have to deal with this,” said director Joel Fendelman.

“Man on Fire” airs Dec. 17 at 10 p.m. EST, on PBS stations across the country, as part of the Independent Lens documentary series. (Some stations will air it later. The film can be seen at PBS.org beginning Dec. 18.)

The producer of “Man on Fire” is James Chase Sanchez, who spent his youth in Grand Saline, named for its vast salt deposits. Sanchez was away at graduate school when he learned of Moore’s fatal act.

He still had plenty of contacts in the small East Texas town. And, almost incredibly, his academic focus was on racism and the rhetoric of sacrifice.

“No one was positioned quite like I was. … I knew I had to tell this story,” said Sanchez, who would shift his dissertation to be largely about Moore, and later collaborated with Fendelman.

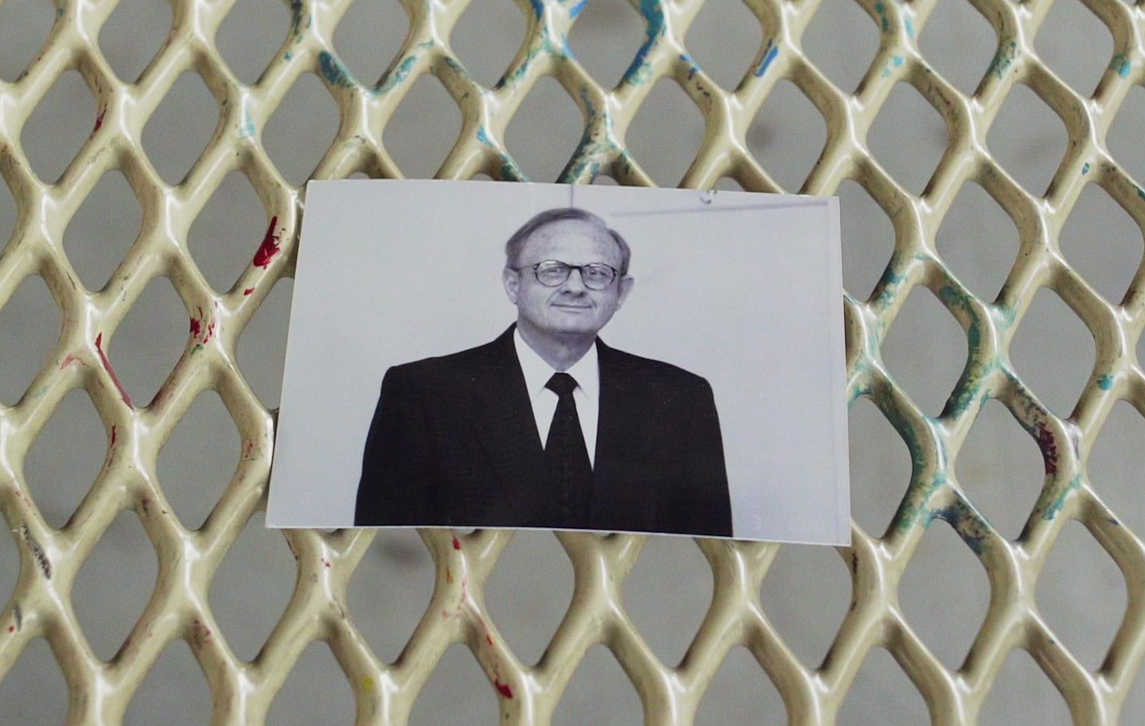

On June 23, 2014, the 79-year-old Moore traveled from his home in Allen, Texas, near Dallas, to Grand Saline. Late in the afternoon, in a shopping center parking lot, he doused himself with gasoline and set himself on fire.

Frantic bystanders found an extinguisher and put out the blaze. Moore was flown by helicopter to Dallas’ Parkland Hospital, but died that night.

He had left a typed note on his windshield calling on Grand Saline to confront its racist past. The note said he was giving his life in hopes the town would address current racial issues.

Family members would later find other notes. One made clear that he had planned to set himself on fire at Dallas’ Southern Methodist University, his alma mater, on Juneteenth, the annual commemoration of the 1865 announcement to slaves within Texas that they had been freed.

“I know that some will judge me insane,” Moore wrote in that note, which also described his love for the school and hope that his sacrifice would prompt more attention to gay rights and the death penalty, as well as fairer treatment of African-Americans.

Moore’s eventual self-immolation in Grand Saline made national news, and Texas Monthly would later do an extensive report, which helped inspire and inform the documentary.

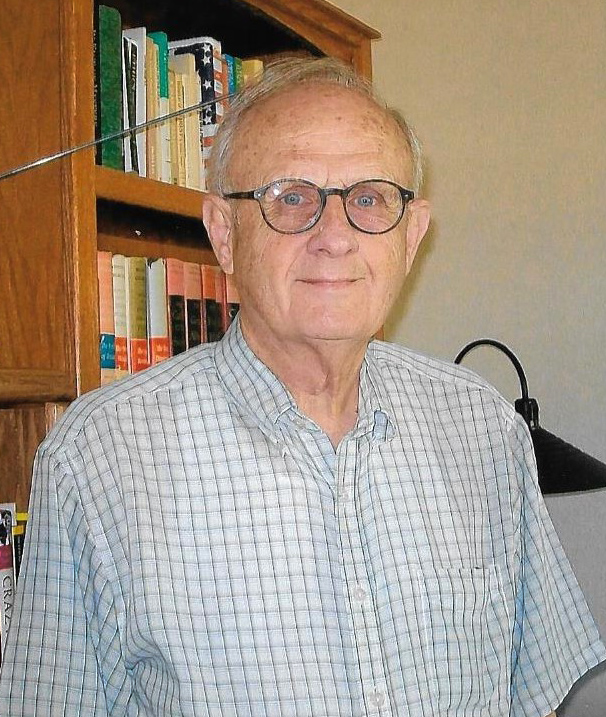

Fendelman and Sanchez draw on their own interviews with family members, pastor colleagues and former parishioners of Moore. These say the longtime elder had a deep, abiding commitment to fighting injustice. One pastor offers that he’d never known anyone who felt injustice to others more than Moore.

His uncompromising career led him into conflict with congregations and supervisors. It included mission work in inner-city Chicago and India.

“He was fearless,” son Guy Moore says in the film.

But the father had clear flaws as well. “He was a part-time father, a full-time minister. And we missed him,” Guy Moore says.

In his last years, Charles Moore was withdrawn, apparently despairing about the state of the world and feeling he’d failed to make much of a contribution. A student of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition of self-sacrifice, he carefully planned how he would die in a last, fiery protest.

Family members remain haunted by what happened. “Man on Fire” also features Grand Saline residents still traumatized by having witnessed Moore’s act.

But while sympathetic to those hurt by Moore, Fendelman and Sanchez also respect his intentions — and take seriously his assertions about Grand Saline. Sanchez had experience to draw on, having been called “wetback” by fellow students. He notes that he joined in casual use of racial epithets.

“It wasn’t until I left Grand Saline that I realized saying the ʽn’ word is bad,” said Sanchez, now teaching at Middlebury College in Vermont.

The film considers, without definitively answering, whether Grand Saline really had a particularly bad record of violence against African-Americans and whether it’s a myth or fact that the town had once had city limit signs warning black people away.

The filmmakers interview white residents who say the town’s reputation was overblown and that race relations are fine now. They hear a very different story from black people, who speak of their elders’ terror about the town, and their own fear of it.

Younger white and black people are interviewed, with some noting the scarcity of black residents in Grand Saline compared to neighboring towns, and the absence of honest conversation about race relations.

Sanchez and Fendelman had challenges making the film. Some people refused to talk. Others agreed but backed out.

“We would show up at someone’s house when they told us to be there, and they wouldn’t be there,” Sanchez said.

Overall, Sanchez and Fendelman felt they were well received, and they’re hopeful that the film will be regarded as fair and balanced by most Grand Saline residents, as well as by Moore’s friends and family.

Sanchez said he thinks “all the time” about a certain line from the civil rights book “Blood Done Sign My Name,” written by Timothy Tyson, a Methodist pastor’s son.

A street in Grand Saline, Texas, the town where the Rev. Charles Moore set himself on fire. He left a note on his windshield that said he was giving his life in hopes the town would address current racial issues. Photo by Joel Fendelman, courtesy of Man on Fire film.

The line is, “If there is to be reconciliation, first there must be truth.”

“We really hope this (film) can foster public conversation, where Grand Saline can admit they have a perception problem, and work together to move past that,” Sanchez said.

Hodges is a Dallas-based writer for United Methodist News Service. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.