On Jan. 2, 1963, 28 white Methodist pastors in Mississippi published a statement titled “Born of Conviction.” It amounted to a declaration of independence from the arch-segregationist views that seemed unassailable in their state.

The swift backlash included death threats, slashed tires and crosses burned in parsonage yards. Within 18 months, 17 of the pastors had bolted the state. Two others departed soon after, and the 20th had left by 1971.

Although big news in Mississippi at the time, the statement would eventually recede into the footnotes of civil rights history. For Joseph T. Reiff (rhymes with “life”), it was buried treasure.

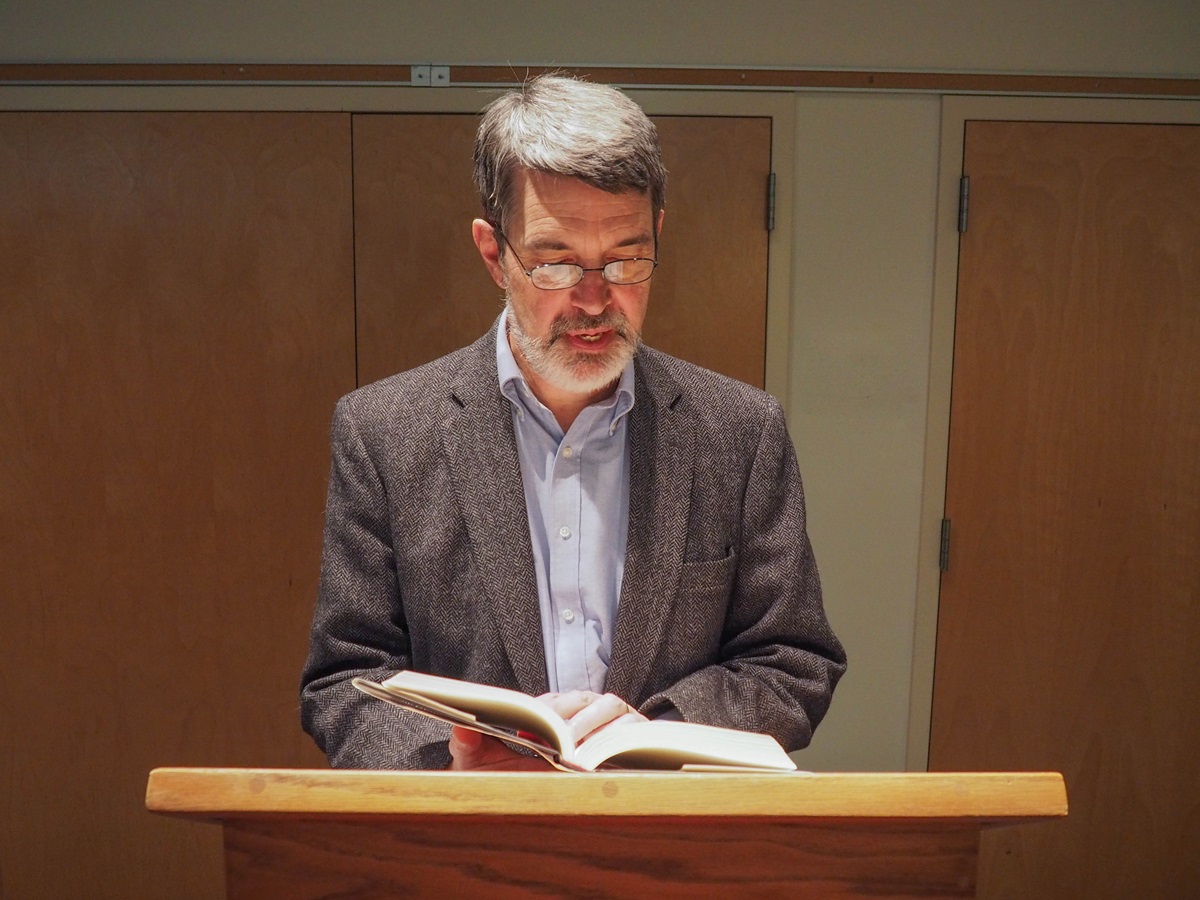

“The story needed to be told, and I thought, ʽI can tell this story,’” he said.

Reiff, a United Methodist elder and religion professor at United Methodist-related Emory & Henry College in Virginia, spent 12 years balancing teaching and administrative duties with researching and writing the new book “Born of Conviction: White Methodists and Mississippi’s Closed Society.”

Published by Oxford University Press, it’s the first full-length, scholarly account of the statement and its aftermath.

Among those grateful for Reiff’s labor is the Rev. Jim Waits, who as a young Mississippi pastor not only signed but also helped craft the statement.

“I’m just impressed with his commitment to this project and his dedication over these many years,” Waits, retired dean of Candler School of Theology, said of Reiff. “He’s done more research than anybody would have ever expected.”

The new book “Born of Conviction” tells of a 1963 statement published by 28 white Methodist pastors of Mississippi, challenging prevailing segregationist views. Dust jacket image courtesy Oxford University Press.

Cracking the ʽClosed Society’

Even among Southern states, Mississippi had a reputation for near lockstep white resistance to integration. “Mississippi: the Closed Society” was the title of a 1964 book by James Silver, a historian at the University of Mississippi. That university had seen two killed and hundreds injured in a Sept. 30, 1962 riot over the imminent enrollment of James Meredith as its first black student.

A cadre of young pastors in the Mississippi Conference felt compelled by events and the gospel to speak out. Waits joined the Revs. Maxie Dunnam, Jerry Furr and Jerry Trigg at Dunnam’s southeast Mississippi fishing cabin and worked up a document of some 600 words.

“Born of the deep conviction of our souls as to what is morally right,” they wrote, “we have been driven to seek the foundations of such convictions in the expressed witness of our Church.”

The statement demanded freedom of the pulpit, affirmed the United Methodist Book of Discipline’s stand against racial discrimination and insisted public schools should be kept open after desegregation. It also expressed opposition to communism.

“You look at the statement now, and it doesn’t seem all that radical,” Reiff said. “But given the context in which it was published, it was.”

The drafters found 24 conference colleagues willing to sign. The statement came out in The Mississippi Methodist Advocate, with editor Sam Ashmore adding a note of support.

But reaction to the statement “was like a bomb exploding,” the Rev. Rod Entrekin, one of the signers, would write later.

Reiff’s book details the suffering some pastors and their families faced, including demands of dismissal, withheld pay and verbal harassment. The Rev. Joe Way and his family were so ostracized by his congregation that his 3-year-old daughter proclaimed tearfully, “Nobody loves us anymore.”

An exodus began, and eventually 20 of the pastors would scatter, with enough going to the Southern California-Arizona Conference that they would constitute a celebrated “Mississippi Mafia.”

But the “spoke out, forced out” narrative is too simple, Reiff writes.

He notes that internal Mississippi Conference politics played a big role in pastors wanting to leave. While some who signed faced hostility from their congregations, others, like Waits, saw little trouble.

Mississippi Conference Bishop Marvin Franklin did not support the signers, but the conference lay leader, J.P. Stafford, stood by them. The faculty of Millsaps College, a Methodist school in Jackson, Mississippi, and alma mater of many of the signers, also offered support.

Reiff argues that the story is all the more nuanced by the fact that eight pastors would remain in Mississippi. Some of those had a hard time, but they felt called to stick it out and work long-term for improved race relations.

“You have to applaud those who did stay,” Waits said. “Many of them had significant ministries on the race question after the statement was issued.”

Did the statement itself bring change, apart from causing or quickening the departure of some of the state’s more progressive pastors?

Reiff believes it at least showed a crack in the Closed Society and gave voice to other white Mississippi Methodists who had moderate to liberal racial views.

He doesn’t equate the pastors’ commitment or risk to that of front-line activists, including Medgar Evers, a black Mississippian and NAACP field secretary who was assassinated in 1963.

“But (the statement signers) paid a price for saying something prophetic to the church,” Reiff said.

A long labor of love

One could make the case that Reiff was born to write “Born of Conviction.” Much of his childhood was in Jackson, where his father, Lee Reiff, taught religion at Millsaps. His mother, Gerry Reiff would, in later years, be an archivist for the Mississippi Conference.

Reiff, 61, would himself attend Millsaps and pastor churches in Mississippi before becoming a professor. As a boy, he watched with his family as police arrested a small group trying to integrate services at their church, Jackson’s Capitol Street Methodist.

“The whole issue of how the white church, especially the white Methodist church, dealt with those issues in the ̛60s has been in the background of my consciousness throughout my life,” Reiff said, noting that his parents were civil rights supporters.

In 2004, Reiff drove around the country to interview surviving signers of the statement. There were 20, and he got interviews with all but one.

Now, with the book finally out, just 14 signers are alive.

Finishing the book took years because of Reiff’s commitments at Emory & Henry, but also because of further research and the challenge of writing a book with 28 protagonists.

“I took too long, but part of it was just trying to get my mind around, ʽHow I can best tell this story? How I can help readers get into it without getting bogged down?’ ” he said.

Reiff has begun to do events related to the book, and he’ll speak at Millsaps on Feb. 18.

He’s been hearing back positively from the surviving pastors.

“One of the signers told me early on that he didn’t think anybody would be interested in this. I think I’ve proved him wrong.”

Hodges, a United Methodist News Service writer, lives in Dallas. Contact him at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.