Key points:

- A summit meeting near Chicago brought about 30 people to discuss the investments Wespath Benefits and Investments makes and forgoes.

- Investment in fossil fuels companies was a focus, with sentiment running high in some church circles that those investments should be avoided because of environmental and other concerns.

- More discussions are planned to hear other voices that have a stake in the issues before the 2028 General Conference takes up the issue.

Eager to avoid a standoff over what investments United Methodists should and should not make, Wespath leaders hosted a summit in hopes of moving toward a consensus before the 2028 General Conference.

At issue is the language in Paragraph 717 in The United Methodist Church’s Book of Discipline that details the denomination’s standards for sustainable and socially responsible investing. Denominational officials and others with a stake in the investment policies joined in the discussion of how delegates at the church’s next lawmaking assembly might amend the paragraph.

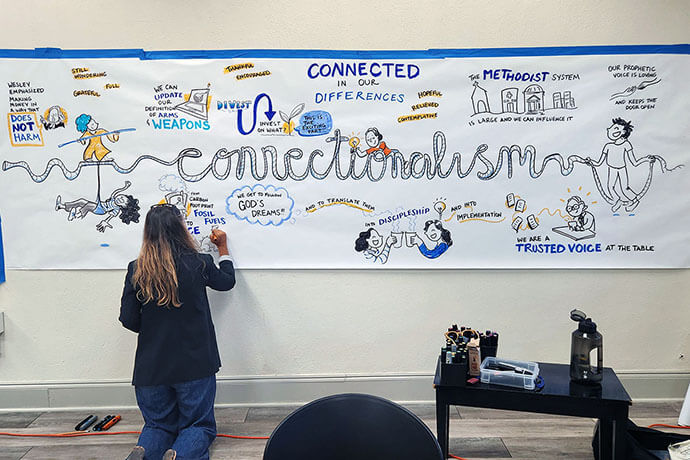

About 30 people attended the summit, held over two days in September at United Methodist-related Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois.

Investment in fossil-fuel corporations was the most discussed topic, but there were others.

“The gathering wasn’t designed to have decisions or results as an outcome,” said Andy Hendren, top executive at Wespath Benefits and Investments. “It was really designed to be more of a beginning of a dialogue, a bridge-building exercise, to create a little safety for some vulnerability … and get a sense of where there are pretty distinct differences.”

Currently, Paragraph 717 instructs United Methodists to “make a conscious effort to invest in institutions, companies, corporations or funds with policies and practices that are socially responsible, consistent with the goals outlined in the Social Principles.”

Specifically mentioned are avoiding investments in weapons, alcohol or tobacco products, private prisons, gambling and pornography.

The closest it gets to fossil-fuel investments is this statement: “The boards and agencies are to give careful consideration to environmental, social and governance factors when making investment decisions.”

Fossil-fuel investments are not specifically tagged to avoid, and some Wespath funds include such stocks.

“We agreed the climate crisis is real, it is urgent and the church is called to answer,” said Sally Vonner, top executive of United Women of Faith, who attended the summit. “We invest through Wespath and partner with them to make sure our heart and our treasure are in the same place: caring for God’s creation.”

Getting fossil fuels added to Paragraph 717 was a priority of many participants, said Tara Barnes, director of denominational relations for UWF. She attended the summit with Vonner.

“There were some good conversations around … the urgency of the crisis,” Barnes added, "and what it means to have a just transition away from fossil fuels"

Bridget Cabrera, executive director of the Methodist Federation for Social Action, confirmed her organization is in the anti-fossil fuels camp. MFSA is an unofficial advocacy group that lobbies The United Methodist Church.

“We believe that (use of fossil fuels) destabilizes the climate and results in an immeasurable harm to both our earth – creation – and humanity,” Cabrera said. “People of color, people suffering from economic insecurity and children are those that often suffer disproportionately from both fossil fuel pollution and climate change.”

Kate Ott, director of the Stead Center for Ethics and Values at Garrett, moderated the meetings and helped set the ground rules.

“Our goals were to build a more thoughtful, holistic approach to engagement of various stakeholders around conversations related to sustainable investment and to diversify the conversation partners,” Ott said. “Everyone had a listening posture and was really open to the challenge of hearing each other for the whole day and a half that we were together.

“None of it got contentious at all.”

Fossil fuels aren’t the only investments that could be troublesome, said the Rev. Neal Christie, executive director of The Religious Nationalism Project and former executive at the United Methodist Board of Church and Society.

The summit took place after Wespath announced in August that it is now avoiding investments in the bonds of some 60 countries based on human-rights concerns.

“I am one of those people who cares about human rights and wants peace with justice for all in Israel and Palestine,” Christie said. “You’ve got people who are focusing on other human rights issues through the Methodist Federation for Social Action.

“I’m on the board of the Native American Caucus. I care about our investments and how they impact Native communities and Indigenous communities around the country.”

Wespath has been steadily working to refine its portfolios to adhere better to Paragraph 717, which makes recommendations but does not require anything. It also holds up investments “that promote racial and gender justice, protect human rights, prevent the use of sweatshop or forced labor, avoid human suffering and preserve the natural world, including mitigating the effects of climate change.”

Christie said he is looking at the good that can be done through investments.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“That is a big way of understanding our investments,” he said. “Wespath sees themselves as having their core mission to care for those who are receiving pensions, and it’s not an ‘either-or.’ They want to see the whole church thrive and do good.

“That’s not a parochial vision. That’s a much bigger vision for the whole church.”

Also, the funds already devoted by Wespath to “clean” investments have performed competitively, Christie said.

“If you look at how well the socially responsible investments have done, they’ve outperformed several of the other funds,” he added.

On the other hand, investment exclusions that are too broad could result in some good asset managers choosing not to do business with Wespath, said Jake Barnett, managing director of sustainable investment strategies for Wespath and its subsidiaries’ investment programs.

“Certain asset managers would say, we no longer want to work with you because you’re cutting off so much of the universe that we can’t replicate the strategy that we have conviction in,” Barnett said.

Another argument to stay invested in fossil fuels is that it gives the church a seat at the table to influence those companies.

“Staying at the table is beneficial when there’s a flaw in the system,” said the Rev. Andy Oliver, a Florida pastor who attended the summit.

But, he added, he sees fossil fuel as the flaw.

“There’s not really much we’re going to tweak within a fossil-fuel world relying on fossil fuels that’s going to change the future of our environment.”

In a Sept. 23 press release, Wespath cited some advancements achieved so far:

- Making investments in affordable housing properties.

- Introducing two new funds for institutional investors with a preference for a heightened focus on climate change and human rights.

- Successfully helping to lobby Chevron to join the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership 2.0, which measures, reports and mitigates methane emissions.

- Reducing the emissions intensity of its investment funds by 48% by Dec. 31, 2024, beating its goal of 35%.

“You could look at it from the negative,” Christie said. “Where are the central conference voices at this meeting? You have one person from the Philippines, and you have one person from Mozambique.” Central conferences are denominational regions in Africa, Europe and the Philippines.

Sosdito Mananze, rector of the United Methodist University of Mozambique, was the only person from an African central conference in Chicago. Clair Aquin Ned Canlas, the treasurer of the Philippines Central Conference, also attended. There were no attendees from Europe.

“The piece that I feel most confident on is that we will have additional conversations with different stakeholders,” Barnett said

“Some of those will be continuing to give participants within Wespath access and talking to our institutional investors. But going beyond that, to really have some of those discussions within the central conferences, talking to groups that haven’t maybe thought as deeply on this subject historically, but might be more impacted by it moving forward.”

At last year’s General Conference in Charlotte, North Carolina, the discussion about Chapter 717 was halted in the last minutes of the assembly and referred to the General Council on Finance and Administration for more deliberation. The denomination’s finance agency, in turn, forwarded that job to Wespath, which oversees the denomination’s sizable investments for retirement benefits.

The work this year is designed to avoid that kind of ending at the General Conference in 2028, said Alajandra Salemi, who was invited to the summit by Hendren after she gave the Young People's Address at the 2024 General Conference.

“The desire is to have one draft of the language, rather than every island creating their own draft that has to be Frankensteined together,” Salemi said. “Instead of talking about just divesting, we’re actually getting an opportunity to invest in a future that we all feel really proud of, in a future that feels healthy and safe for all of us.”

Bishop Tom Berlin of the Florida Conference attended the summit. He said it was part and parcel of a new age of United Methodism.

“I think the last 10 years, The United Methodist Church has been largely defined by conflict and fracturing,” Berlin said. “I think this new United Methodist Church can be defined by collaboration, candor and shared values. … While we may not fully agree when we walk out of the room, we can get to better outcomes and better alternatives … and understand that the values that we’re acting out of are actually shared values, but that the strategies we want to put forward may vary.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free UM News Digest.