Pontos chave:

• Pessoas que não confiam em outras instituições ainda podem confiar que os líderes religiosos abordarão suas preocupações sobre a vacinação COVID-19.

• Patrocinar vacinações móveis, hospedar discussões na comunidade e compartilhar testemunhos em vídeo sobre porque os membros escolheram ser vacinados são medidas práticas que as igrejas podem tomar.

O presidente Joe Biden estabeleceu uma meta nacional de 70% dos adultos norte-americanos com pelo menos uma dose da vacina COVID-19 até 4 de julho, e ele espera que a comunidade religiosa ajude a alcançá-la.

Atualmente, 64% da população adulta recebeu a primeira dose da vacina. Biden declarou um “mês nacional de ação” nos 30 dias que antecederam o Dia da Independência e está buscando organizações nacionais e comunitárias, incluindo a comunidade religiosa, para encorajar a vacinação.

Durante uma cúpula on-line em 26 de maio organizada pela Faiths4Vaccines, uma iniciativa nacional de várias religiões, o cirurgião-geral dos Estados Unidos Vivek Murthy disse aos participantes: “Em um momento em que as pessoas estão procurando informações e se perguntando em quem podem confiar... eles procuram pessoas que conhecem, por pessoas em quem confiam”, e que os líderes religiosos têm a confiança de suas comunidades. Uma tendência preocupante é que, embora as vacinas estejam muito mais amplamente disponíveis do que há alguns meses, as taxas de vacinação têm diminuído. Muito disso se deve à desconfiança médica e hesitação dos indivíduos em receber a injeção.

É aqui que as igrejas podem desempenhar um papel importante.

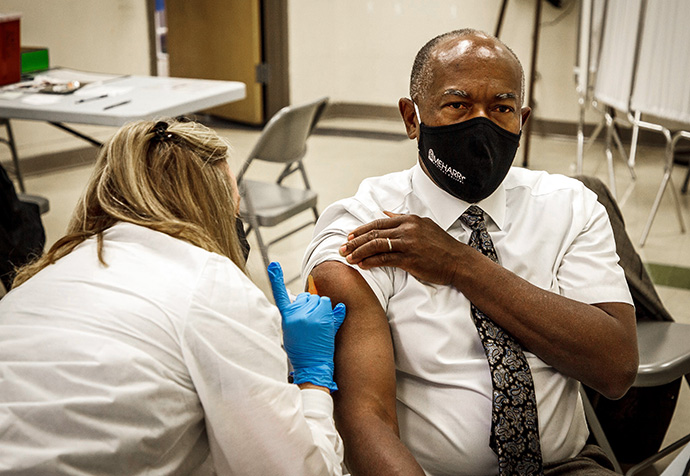

Tia Moore, uma enfermeira, prepara uma dose da vacina COVID-19 durante uma clínica de vacinação na Faculdade de Medicina Meharry em Nashville, Tennessee, em março. A escola ligada à Metodista Unida tem servido como local de vacinação desde janeiro e opera uma clínica móvel de vacinas.

“O ambiente no qual você recebe a vacina é importante porque as pessoas querem estar onde se sentem confortáveis e as igrejas representam um lugar de conforto e segurança para muitas pessoas”, disse o Dr. James EK Hildreth, presidente e diretor executivo da Faculdade de Medicina Meharry em Nashville, Tennessee. A escola de medicina historicamente negra é apoiada pelo The Black College Fund (O Fundo da Faculdade Negra) da Igreja Metodista Unida.

Meharry tem servido como local de vacinação desde janeiro e também opera uma clínica móvel de vacinas.

“Por estar localizado em um bairro predominantemente afro-americano, a desconfiança médica é um problema”, disse Cat Nash, que atua como líder clínico para vacinações na escola. “As igrejas emprestam credibilidade e o clero, é uma boa maneira de chegar aos pacientes.”

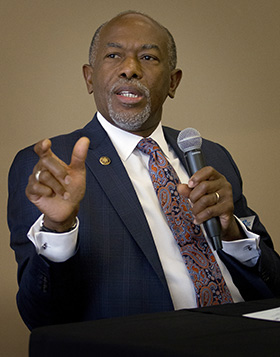

O Dr. James Hildreth, presidente da Faculdade de Medicina Meharry em Nashville, Tennessee, recebe a vacinação COVID-19 em uma clínica municipal em dezembro de 2020. Hildreth disse em reportagens na época que recebeu a vacina diante das câmeras para demonstrar sua confiança em sua segurança. Foto cedida pela Meharry Medical College.

Hildreth concordou. “O mais urgente é que alguém chame a atenção das pessoas que estão resistindo, apenas para responder às perguntas”, disse ele.

Embora reconheça as preocupações daqueles que estão hesitantes, Hildreth aponta que mais de 2 bilhões de vacinas foram administradas em todo o mundo, “então ninguém mais é uma 'cobaia'. Os efeitos adversos são extremamente raros.”

Perfil

O Dr. James EK Hildreth, presidente e CEO da Faculdade de Medicina Meharry, está envolvido com o desenvolvimento da vacina COVID-19 desde o início. Ele atua no comitê da Food and Drug Administration que analisa vacinas e recomenda a aprovação, e liderou vários testes de vacinas em Meharry. Em fevereiro, ele foi nomeado para a Força-Tarefa COVID-19 Health Equity da Casa Branca.

Segundo ele, o trabalho da força-tarefa se divide em três áreas: as comunicações, as próprias desigualdades e o que as causou.

“Tentamos encontrar os indivíduos ou organizações mais adequados para falar com as pessoas mais afetadas pelo COVID-19”, disse ele, “então verificamos como garantir que os recursos que foram oferecidos para o COVID-19 sejam distribuídos de forma equitativa. Por fim, perguntamos quais foram os fatores que causaram tais disparidades na doença e morte de COVID-19.”

“As disparidades de saúde em nosso país não foram causadas pelo COVID-19, elas eram pré-existentes e o COVID-19 apenas as explorou”, disse ele.

A força-tarefa de 12 membros - que reúne líderes em medicina e em políticas públicas e defesa de direitos - ouve especialistas em áreas que lidam com essas questões. Com base nessas conversas, o grupo vai gerar recomendações para o governo Biden.

Observando que ele não fala pela força-tarefa, apenas como um membro individual, Hildreth disse: “Estou muito animado com a possibilidade de fazer recomendações que terão um impacto de longo prazo, para que da próxima vez que tenhamos um crise nacional de saúde, não falemos de pardos e negros sendo os mais afetados”.

- Joey Butler, Notícias MU.

Maus tratos históricos a afro-americanos pela comunidade médica - o experimento Tuskegee e o Hospital Johns Hopkins colhendo as células de Henrietta Lacks são exemplos bem conhecidos - fez com que muitos tivessem dificuldade em confiar nos médicos. A desinformação também pode ser difícil de superar. Alguns estão simplesmente preocupados com a dor ou doença causada pela injeção.

“O maior problema são as pessoas que ouvem falar de um amigo que teve uma reação ruim ou boatos, e põem na cabeça que não querem isso”, disse Nash. “As pessoas se preocupam com os efeitos colaterais da segunda dose porque eles variam muito.”

Cerca de 65% não têm nenhuma reação, disse Carl Wood, presidente e gerente de farmácia da Vax Van by MVS, uma clínica móvel de vacinação em parceria com as igrejas Metodistas Unidas em Charlotte, Carolina do Norte.

“Quando falo com as pessoas sobre isso, muitas vezes as convence de que está tudo bem”, disse ele.

Wood disse que os líderes religiosos que se vacinam dão o exemplo: “Se a liderança da igreja der suas vacinas, alguém pode dizer: 'Também posso me sentir seguro'”.

Os jovens são outro grupo que demorou a ser vacinado.

Os irmãos Ashlee Hand, 20, e Walter Hand III, 18, foram vacinados e trabalharam em uma clínica de vacinação em 30 de abril realizada na Igreja Metodista Unida de São Marcos em Charlotte. Eles disseram que as pessoas em sua faixa etária muitas vezes ouvem informações incorretas ou pensam que os jovens não precisam se preocupar em pegar COVID-19.

“Muitos dos meus amigos estão recebendo informações falsas (sobre a vacinação), ou seus pais não querem que eles as obtenham. Muitos acham que têm imunidade”, disse Ashlee Hand.

Walter Hand disse que alguns de seus amigos foram vacinados e ele tenta encorajar outros a fazerem o mesmo.

“Eu digo a eles que acho que tomar a vacina me permitiu fazer mais coisas, me sentir mais seguro ao sair”, disse ele.

Problemas semelhantes de hesitação existem na comunidade latina, muitas vezes devido à desinformação. Muitos estão preocupados com o fato de que serão solicitados comprovantes de cidadania para obter a vacina, o que leva a preocupações de que um grande número de imigrantes sem documentos permanecerá não vacinado. Também pode ser desconfortável para quem não fala inglês se ninguém que fale seu idioma estiver presente, portanto, ter tradutores à mão é essencial.

As igrejas também estão alcançando outras comunidades marginalizadas.

A Igreja Metodista Unida New Hope em Des Moines, Iowa, hospedou uma clínica de vacinação organizada pela Sociedade Americana Filipino de Iowa. Voltada para a comunidade asiático-americana e das ilhas do Pacífico, a clínica contou com intérpretes em cinco idiomas.

A Conferência Missionária Indiana de Oklahoma fez parceria com unidades federais de Serviços de Saúde Indígena para fornecer vacinas aos nativos americanos.

De acordo com o reverendo David Wilson, superintendente da conferência, a demanda por vacinas diminuiu drasticamente - a tal ponto que o estado está prestes a perder milhares de doses até o vencimento.

“Ontem estive no local por uma hora e havia apenas quatro pessoas”, disse ele. “Oklahoma estará muito abaixo dos níveis que precisamos alcançar. Não sei se as pessoas perderam o interesse ou se acham que estão bem.”

Igrejas e grupos estão fazendo campanhas para educar e exortar as pessoas a se vacinarem.

Wilson, que atua no conselho da Clínica Indígena de Oklahoma City, disse que ela está oferecendo vacinas em uma refeição semanal para os sem-teto, uma escola autônoma de índios americanos e até mesmo um mercado de fazendeiros na cidade.

“Estou tentando em qualquer lugar quando vejo sites ou eventos onde haverá um grande número de pessoas”, disse ele.

Embora a hesitação pareça ser a maior barreira, questões práticas de desigualdade também existem para muitas comunidades. Pode ser difícil tirar uma folga de um trabalho por hora. Muitos lutam com problemas de transporte ou podem estar presos em casa e morando sozinhos.

Carl Wood administra uma dose da vacina Moderna COVID-19 durante uma clínica na Igreja Metodista Unida de São Marcos em Charlotte, NC, em abril. Wood disse que os líderes religiosos que se vacinam são um exemplo: “Se a liderança da igreja tomar suas vacinas, alguém pode dizer: 'Também posso me sentir seguro'”.

As igrejas que hospedam clínicas de vacinas em seus prédios podem ter que viver segundo o lema de “conhecer as pessoas onde elas estão”, aventurando-se na comunidade.

Em sua cúpula online, Faiths4Vaccines listou uma série de maneiras práticas pelas quais as igrejas podem quebrar barreiras e hesitações e aumentar o acesso às vacinas.

Cat Nash, uma médica assistente, é a líder clínica da clínica de vacinação COVID-19 na Faculdade de Medicina Meharry em Nashville, Tennessee. Ela é membro da Igreja Metodista Unida de Brentwood (Tennessee).

Algumas das sugestões para igrejas incluem:

• Oferecer transporte para clínicas ou patrocinar clínicas móveis para viajar para bairros carentes;

• Campanha de porta em porta na comunidade da igreja para compartilhar informações sobre vacinas;

• Hospedar eventos informativos e conversas abertas sobre a vacina;

• Gravar depoimentos sobre porque as pessoas optaram por receber a vacina e compartilhá-los nas redes sociais.

Uma barreira que preocupa Hildreth é a realidade de que as opiniões políticas de uma pessoa podem levar seu raciocínio a não se vacinar. O vírus, observa ele, “é agnóstico em relação à sua filiação política”.

“Qualquer pessoa que possa efetivamente envolver este grupo nessa conversa, precisamos que o faça, e que o faça em breve”, disse ele. “Se não vacinarmos os 30 a 40% das pessoas restantes e o vírus passar por esse grupo, ainda existe o perigo de surgirem variantes para as quais as vacinas não fazem muito.”

Embora as vacinas estejam disponíveis para quase todas as pessoas nos países mais ricos, há uma desigualdade significativa nas nações mais pobres - uma questão sobre a qual Hildreth disse que a Igreja deveria se manifestar.

“Os países ricos do planeta precisam comprar a vacina e dá-la aos países que não podem pagar, porque nenhum de nós está seguro até que todos estejamos seguros”, disse ele. “Como população global, precisamos que todos sejam vacinados.”

Walter Hand III recebe a vacinação COVID-19 do EMT Archie Coble durante uma clínica na Igreja Metodista Unida de São Marcos em Charlotte, NC, em abril.

* Butler é produtor / editor de multimídia e DuBose é fotógrafo da equipe da Notícias MU. Contate-os em (615) 742-5470 ou newsdesk@umcom.org. Para ler mais notícias da Metodista Unida, assine os resumos quinzenais gratuitos.

** Sara de Paula é tradutora independente. Para contatá-la, escreva para IMU_Hispana-Latina@umcom.org.