Key points

- Jovita Idár was a Mexican American journalist and activist — and faithful Methodist — working in South Texas in the early 20th century.

- Her heroic efforts to advance the rights of Mexican Americans and women, as well as her attention to child welfare, have gained increasing attention in recent years.

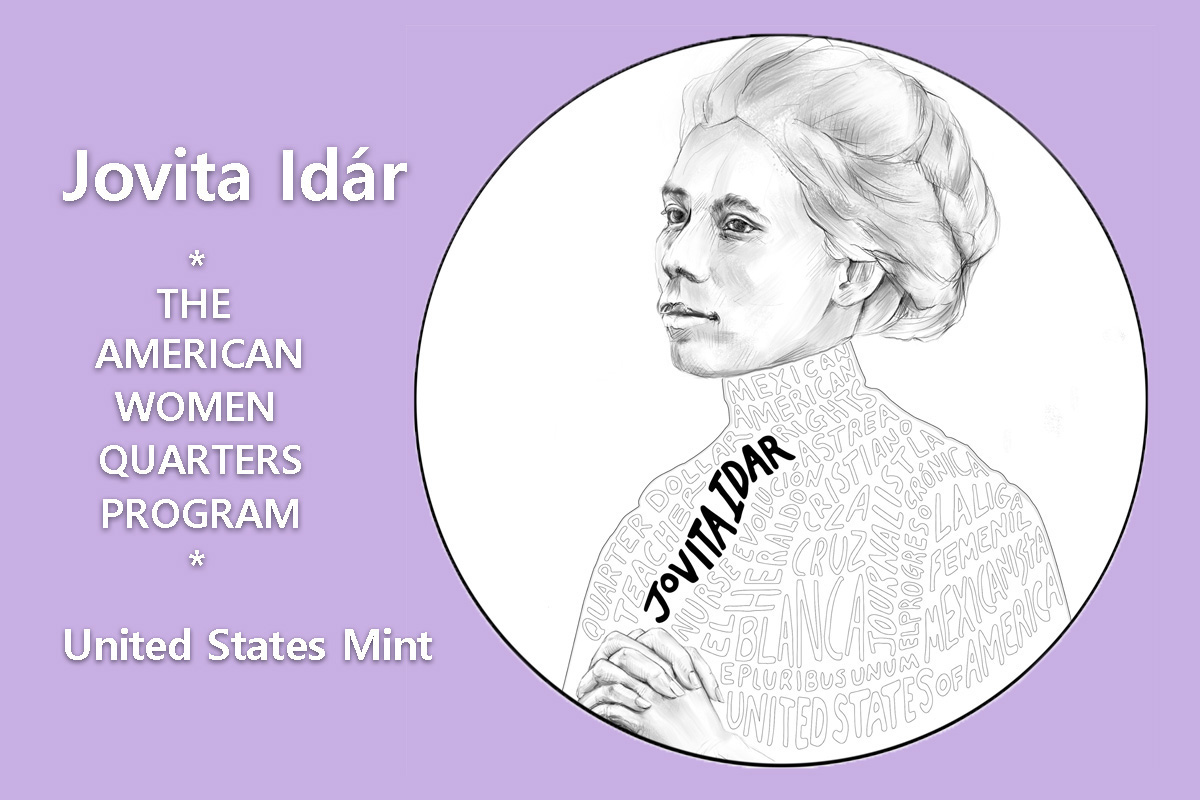

- The United States Mint has included her as part of the American Women Quarters series, along with Eleanor Roosevelt, Maya Angelou and Sally Ride.

Fame is catching up with Jovita Idár. One might even say she’s having a moment, 76 years after her death.

Idár’s life as a Mexican American journalist and activist in South Texas began to be rediscovered in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as attention to women’s and ethnic history grew.

Though she’s still not a household name, Idár’s heroic advocacy for Mexican Americans, as well as for women and children, has made her the subject of scholarly articles, a documentary and a historical marker. The city of Laredo, Texas, named a park in her honor in 2020.

That same year, The New York Times featured her in its Overlooked No More project recognizing historical figures who should have gotten a Times obituary right after their deaths, but didn’t.

This year has brought a major development: The United States Mint’s inclusion of Idár in the American Women Quarters series. In 2023, she’ll have her image on a special-issue coin, joining Eleanor Roosevelt, Maya Angelou, Sally Ride and others.

Gabriela González is at work on a biography of Idár, and she realizes she has a wave to catch.

“I’ve got to hurry up,” said González, a historian at the University of Texas at San Antonio. “She’s becoming more and more popular. It’s amazing.”

Not lost in the shuffle, exactly — but also not always emphasized — is that Idár was a lifelong, faithful Methodist.

González considers Methodism to have been, with modernism and liberalism, a shaping force in Idár’s life.

And when retired United Methodist Bishop Joel Martinez thinks about Idár, he’s reminded of Susanna Wesley, the mother of Methodism founders John and Charles Wesley, and a multifaceted Christian leader herself.

“I just have that echo in mind,” Martinez said.

Idár was born into a large, educated, relatively well-off Mexican American family on Sept. 7, 1885, in Laredo, Texas. Her maternal grandfather was the Rev. Clemente Abraham Vivero, a Methodist minister. Her father, Nicasio Idár, was mentored by Vivero but pursued secular careers, eventually publishing a Spanish-language newspaper in Laredo — La Crónica.

In her youth, Jovita Idár attended Laredo Seminary, a Methodist school that would become known as Holding Institute, after the school’s Methodist missionary leader Nannie Emory Holding. After graduating in 1903, Idár taught impoverished Mexican American children in tiny Los Ojuelos, Texas.

But she didn’t teach for long, instead joining her father’s newspaper.

“Appalled by the poor conditions and inadequate equipment as well as the lack of hope in this community, she resigned and turned to political journalism, working alongside her brothers and father and using the media to foment social change,” González wrote in a chapter on Idár for the book “Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives.”

At La Crónica, Idár reported on and editorialized against the poverty and discrimination faced by Mexican Americans, including school segregation and even lynching. She decried the denigration of the Spanish language and Mexican culture. Using pen names such as Ave Negra (black bird) and Astrea (Greek goddess of justice), she championed equal rights for women, including the right to vote.

More on Jovita Idár

An 11-minute documentary on Jovita Idár is part of the Unladylike2020 series. Gabriela González, who is writing a biography of Idár, is interviewed. González wrote extensively about the Idár family in an earlier book, “Redeeming La Raza: Transborder Modernity, Race, Respectability, and Rights.”

Idár went beyond the journalist’s role, helping to organize El Primer Congreso Mexicanista (First Mexican Congress), a 1911 gathering of Mexican American activists from both sides of the border. Out of that came Liga Femenil Mexicanista, the Mexican Women’s League, and Idár was its founding president.

Along the way, she developed a motto: “Educate a woman and you educate a family.”

Surely the most cinematic moment of Idár’s career came in 1914, when El Progreso, the Laredo newspaper she was then working for, published an editorial critical of President Woodrow Wilson for ordering a U.S. military occupation in Veracruz, Mexico.

A team of Texas Rangers soon arrived at the newspaper, intending to shut it down in retaliation. They had a surprise.

“One of (El Progreso’s) writers, a slender, twenty-nine-year-old woman named Jovita Idár, stood in the doorway to block them. As a crowd formed, the Rangers backed away,” wrote Doug J. Swanson in his 2020 book “Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers.”

They soon returned, when Idár and other staff members weren’t there, and destroyed the printing press. But her stand against the Texas Rangers would become a defining anecdote when historians and others began to share about her life.

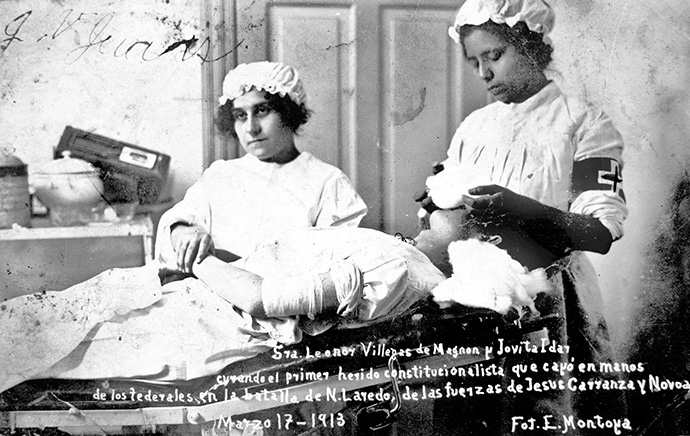

The prolonged, bloody Mexican Revolution also was a huge event for Idár, and she wrote against the entrenched, anti-democratic government. Here, too, she was a woman of action, as part of La Cruz Blanca (the White Cross), a medical relief group. She didn’t just organize but put on a white uniform and joined in caring for the wounded in Nuevo Laredo, across the border in Mexico.

Idár married Bartolo Juarez in 1917, and within a few years they moved to San Antonio. There she worked as a translator. She also was active at La Trinidad Methodist Church and co-edited Heraldo Cristiano, the newspaper of the Rio Grande Conference of the Methodist Church.

Though she had no children, she helped raise the two daughters of her late sister, Elvira Idár Fuentes.

Among Jovita Idár’s great nieces is the Rev. Liz Lopez, a retired United Methodist pastor and district superintendent who was born after Idár’s 1946 death but felt she knew her through hearing family stories.

“We talked about our Tía (Aunt) Jovita like she was in the next room,” Lopez said.

Another great-niece, Dalinda R. Gonzales, also felt Idár’s influence.

“Through stories of her ingenuity, education and bravery, my great aunt affected my ideas and decisions,” Gonzales said. “She left me with a mind ready to try anything!”

Idár found in Methodism a social holiness emphasis, consistent with the social gospel movement of her era.

“I would say that for Jovita, part of living out her Methodism was helping others,” said Professor González, the historian. “Prayer was very important, of course, but it was also about doing what Jesus would have done.”

While it’s hard to be definitive about what sparked the growing interest in Jovita Idár, the late 1970s and early 1980s saw the preparation of a major exhibition on the history of Texas women — and Idár was part of it.

Mary Beth Rogers, a well-known Texas author and political organizer, led the effort. She and her team had a strong commitment to including women of color.

Rogers credits colleagues Martha Cotera and Ruthe Weingarten with putting forward Idár after encountering her in the old Spanish-language newspapers of South Texas.

“Jovita’s story was there awaiting discovery,” Rogers said.

And the discovery goes on.

Hodges is a Dallas-based writer for United Methodist News. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.