Key Points:

- A study of 87 rural churches in North Carolina suggests that each rural church contributes between $488,598 to $735,000 of value to its local economy each year.

- Rural churches support local businesses and provide community meeting space, early childhood education and more.

- The economic contributions of rural churches suggest they should be measured by more than the length of their membership rolls.

A new study suggests there’s a whole lot of valuable things going on in rural churches — including smaller congregations — beyond Sunday morning worship.

In North Carolina, a rural church contributes between $488,598 to $735,000 of value to its local economy each year, according to a new study from Partners for Sacred Places and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute prepared for The Duke Endowment. Eighty-seven churches in North Carolina were surveyed for the study, “The Economic Halo Effect of Rural United Methodist Churches of North Carolina.” For the purposes of the study, “rural” was defined as “counties with a population density of less than 500 people-per-square-mile.”

“I would say that it's a report that some people would find quite surprising,” said Randy Wall, chairperson of United Methodist Rural Advocates, an organization that seeks to advocate, educate, inspire and influence The United Methodist Church around rural issues.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“(Rural churches are) more than places where people … come to be patched, matched or dispatched,” he said. “(The study) helps all of us, including myself, to see the value of rural churches in ways that perhaps a lot of folks haven't considered.”

The economic value that rural churches bring to their communities, according to the study, includes:

- Supporting local businesses;

- Acting as a community hub, providing space to solve problems and build social capital;

- Providing early childhood education, many times in areas underserved by child care centers;

- Counseling and supporting people and families struggling with a range of issues;

- Attracting visitors to cities and towns where the churches are located, with almost half of those visits unrelated to worship;

- Employing people, on average 1.4 fulltime employees and four part-timers;

- Purchasing goods and services from local businesses.

“All these findings add up to a larger, remarkable — but little known — reality,” the report reads. “UMC congregations, quietly and faithfully, constitute an important part of the fabric of rural communities. We cannot afford to take them for granted. And when they need our support or a helping hand, we should be more open to giving it.”

There are some limitations of the study that warrant mention, the authors noted in the report. The authors are Rachel Hildebrandt, Emily Sajdak and Bob Jaeger of Partners for Sacred Places, and Katie Zager and Angelique Gaines of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

For one thing, the churches surveyed are all in North Carolina, and economic circumstances vary elsewhere.

“Congregations included in the study were selected by conducting a random sampling of rural United Methodist congregations eligible for the Duke Endowment’s Rural Church program,” the report said. “These churches were then asked to participate. The findings, therefore, speak to the congregations that chose to participate in this study and do not represent the characteristics and activities of all rural churches.”

The $735,000 figure was determined by averaging the results of all 87 churches surveyed. The more conservative $488,598 number is the result of removing outlier churches from either end of the spectrum, which reduced the sample to 69 churches.

“Applying (the results) to the wider group of 1,283 churches, this represents a total of $626 million across North Carolina each year,” said the report.

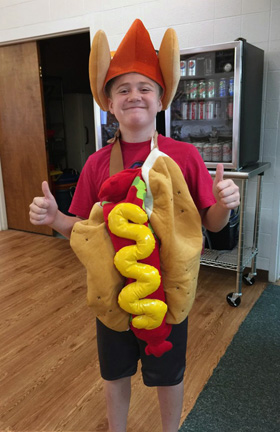

Gethsemane United Methodist Church in Greensboro participated in the study. In addition to its weekly services, the church holds a hot dog luncheon every other Saturday. It’s affectionately known in town as “The Hot Dog Church.”

The church has about 130 members; hot dog Saturdays draw about 200 or so. Before COVID-19, it was even more.

“It's an exciting place to be on a Saturday,” said the Rev. Sharon Lee, pastor of Gethsemane. “Every time we open the doors for hot dogs, we're meeting new people.”

Greensboro is a growing area, with new subdivisions being filled up nearly as fast as they can be built. Its population is more than 300,000.

“We are located on the outskirts of Greensboro with a Greensboro zip code in what has been defined historically as rural, which is why we were chosen for the study,” Lee said. “Yet, we are seeing significant growth in our area as the land is being sold and new housing developments are going in along with retail.”

Gethsemane wants to welcome all the newcomers, Lee said. But there is no hard sell to try and get newcomers to join the church, she added.

“We do believe in United Methodism that if you hear our story and you experience our fellowship … that you will want to be part of us,” Lee said. “We have found people have come to worship on Sunday through the hot dog experience, but it's not an intention that we set out to try to gain members.”

Direct spending in the community is the largest economic value rural churches bring, at 25%. But there’s also money coming in from education and child care, community-serving programs and recreational space.

The report could be encouragement to look at metrics other than membership numbers and giving to measure the effectiveness of a church or pastor.

“I think (the report) really increased our confidence level,” Lee said. “I think that's one of the things that we're encouraging, for folks to look at churches differently.”

The Rev. Laceye Warner, a professor at Duke Divinity School who co-wrote an essay on Methodism in North Carolina in the study, said the results could be read as a mandate for United Methodist churches to widen their scope.

“I do think it's an invitation to say, ‘Hey, wait, what are we doing with our resources? If we're going to have a building and pay all the overhead costs that comes with that, then let's put that to faithful ministry use.’”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.