Key points:

• The complex story of Methodism in England and colonial America finds a juncture at Old South Presbyterian Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

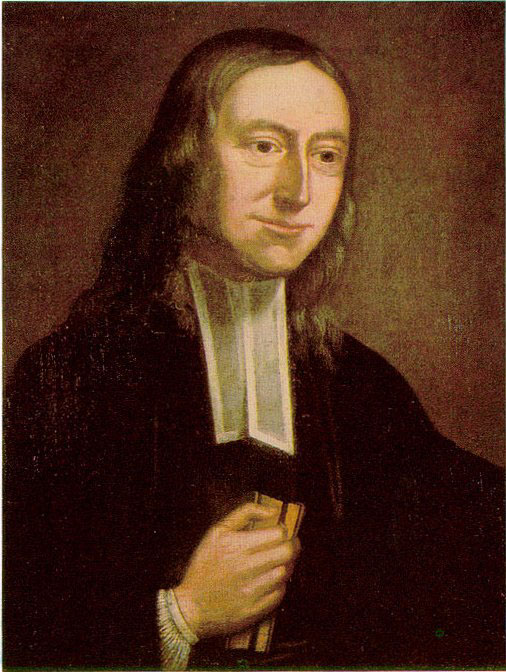

• George Whitefield, who founded and had a 30-year connection to the church, is buried beneath its pulpit.

• Whitefield was a protégé and sometimes rival of John Wesley, even pastoring in Savannah, Georgia, after Wesley returned to England.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Commentaries

One evening, the Rev. John Wesley preached from atop his father Samuel’s tomb in the churchyard of St. Andrew’s Church in Epworth, Lincolnshire.

Today, the Rev. Laurel Cockrill preaches each Sunday from atop the tomb of John Wesley’s protégé and rival, the Rev. George Whitefield. Her pulpit, at the Old South Presbyterian Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts, lies directly above Mr. Whitefield’s tomb.

Oddly enough, the complex story of Methodism in England and colonial America finds a juncture in this New England Presbyterian church. Three legendary figures of the 18th century’s Great Awakening — John and Charles Wesley and George Whitefield — are featured.

I’ve been led to their story through a photo Laurel Cockrill posted of herself.

I came to know her while I was her Fuller Seminary Apprenticeship Group leader. Examining the photo, I noticed that engraved on the pulpit were the words, “Under This Pulpit Are Deposited the Remains of the Reverend George Whitefield.”

As a Methodist, I thought to myself, “Our English Methodist George Whitefield? Why is he buried beneath a Massachusetts Presbyterian Church?”

To answer the questions, I’ve learned more of the sometimes-conflicting relationship between Wesleyan Methodism, espoused by John and Charles, and Calvinistic Methodism, espoused by Whitefield.

The Old South Church of Newburyport was indeed founded by Whitefield. Not unlike John Wesley’s being barred from preaching from the pulpit of his late father’s church, George Whitefield was similarly barred from speaking in local Anglican churches. Like Wesley, Whitefield was deemed “too enthusiastic.”

In an age when much parish preaching was dry, local clergy protected their pulpits from itinerant evangelists by saying they were not preaching in their assigned parishes. We recall John Wesley’s defiant response: “The world is my parish.” Whitefield’s demeanor was similar. Though we may look at Wesley’s statement as benign, the truth is that he and Whitefield threatened well-entrenched local clergy.

In 1740, already a famed preacher, Whitefield first preached in the Newburyport community. However, when he returned, local churches barred him. Whitefield was not dissuaded. He chose to “field preach” and the crowds flocked to him. The outcome was a deeper faith in Jesus that crossed denominational lines and led to the organization of what is today the “First Presbyterian (Old South) Church” of Newburyport.

Six years after Whitefield’s visit, the church called its pastor, the Rev. Jonathan Parsons. Not only was his name “Parsons” ideal, so were his gifts and graces. He served the church from 1746 until his death in 1776. An advocate for American independence, he fittingly died on the day that the Declaration of Independence reached Newburyport.

Highlighting his ministry was the erection of the 1756 church building, built by a volunteer team of 150 people in three days. Virtually all the original church structure remains. With much of the town’s residents being shipbuilders, they were perfectly skilled to build this lasting House of God. The church is famed for its church bell, cast by Paul Revere, which is rung to this day. Under the influence of its patriotic pastor, Jonathan Parsons, the first company of volunteers for the Continental Army assembled in the church on April 23, 1775.

Today, the church’s Presbyterian identity fits its independent origin and Calvinistic influence. Laurel mentioned that though the congregation is justifiably proud of its place in history and remarkable building, it desires to be more than a tourist attraction. The congregation is discovering new, creative ways to further the cause of Christ.

The interweaving of the Wesleys and Whitefield begins at Oxford University. John and Charles received their bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Oxford, both matriculating at Christ Church College. Charles began the famed Holy Club and quickly asked his older brother John, already a fellow at Lincoln College, to be its leader. In 1729, the club was dubbed “The Oxford Methodists,” the name that stuck not only for the club, but also for “The People Called Methodist.”

George Whitefield entered Oxford’s Pembroke College in 1732. A young man of modest means, he found his way to the Oxford Methodists. He was especially drawn to John Wesley, 11 years his senior, who became his mentor.

Now comes the moment that changed the Wesley and Whitefield lives. James Oglethorpe, a member of the House of Commons, successfully advocated in 1732 for the establishment of the first new American colony in 50 years. Its charter, signed by King George II, bears his name: the colony of Georgia. Oglethorpe became its governor.

Oglethorpe, who was a friend of the Rev. Samuel Wesley, shared John Wesley’s passions for prison reform and the concerns of the poor. Oglethorpe invited him to serve Christ Church, Savannah and the needs of the Native Americans. Oglethorpe then invited Charles Wesley to serve as his secretary and chaplain to St. Simons Island. The brothers agreed, invited Whitefield to lead the Oxford Methodists, and sailed for Savannah, arriving in 1735.

It’s fair to say that Gov. Oglethorpe and the Wesleys came to regret this relationship. At this time, the brothers were dogmatic in how people should practice their faith. Even on board the ship, their obsession drove Oglethorpe to write of them, “They unroll their rolled-up rules for England” and pass it on to the passengers. Their obsession did not end once they reached the 13th colony.

Charles lasted but six months in Georgia. He was critical of Oglethorpe’s character and found the duties of a secretary did not match his skill set. John continued in Savannah, going so far as to invite Whitefield to join him, an invitation Whitefield accepted.

But then, John Wesley met Sophia Hopkey, his “Miss Sophy.” They were taken with each other and appeared to be on the way to marriage. It was not to be. Possibly influenced by the Moravians, Wesley decided that marriage might distract him from his ministry. Miss Sophy did not wait for Wesley, quickly marrying another gentleman. This led the miffed Wesley to refuse her communion. Hopkey’s family was incensed, and Wesley was miserable. The result was Wesley leaving Georgia in late 1737, never again to return to America.

Though he was a broken man, his faith was restored by the Aldersgate experience, which occurred just five months later in London. Wesley, “saved by grace,” advocated God’s grace available to all, free will and sanctification — principles that eventually led to his fallout with Whitefield.

By 1742, John Wesley’s fame was well-established. His itinerating style eventually led him to his boyhood church, St. Andrew’s in Epworth, Lincolnshire, where his father had served from 1697 until his 1735 death. On June 6, 1742, Wesley expressed to Mr. Romley, the church’s curate, his willingness to either lead prayers or preach. Romley declined the offer, so Wesley, no shrinking violet, chose to preach from atop his father’s grave.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

In 1738, Whitefield arrived in Savannah only to find that John Wesley had returned to England. In a fascinating twist, Whitefield was installed as Wesley’s successor, serving Christ Church for the next two years until his own return to England. These were the first two of Whitefield’s 13 sailings across the Atlantic.

Trained in theater and theology, Whitefield became an international celebrity. His booming voice was said to be heard from a mile away. His focus on large events and advance publicity foreshadowed contemporary evangelists. Upwards of 20,000 persons — most notably on the Boston Common, Oct. 12, 1740 — heard him preach at a single event. The Boston event was less than two weeks after Whitefield first visited Newburyport. He came to be known as “The Grand Itinerant,” even twice preaching from Jonathan Edwards’ pulpit in Northampton.

Though John Wesley and Whitefield were kindred spirits in their Oxford Methodist days, their breach was secured in 1741. Wesley’s understanding of free grace and free will and his understanding of sanctification led him to an open approach to the faith. From this flowed his commitment to social justice.

Whitefield, possibly under the influence of Puritan authors, embraced a Calvinistic Predestination and Divine Initiative approach to faith. Of John Wesley, Whitefield scornfully wrote, “He and I preach two different gospels.” Though the two never fully reconciled, it is touching to note that John Wesley preached the sermon for Whitefield’s 1770 London funeral. Whitefield was buried in Old South Church, Newburyport, with 8,000 in attendance.

Whitefield’s influence in America cannot be overstated. It is said that by the time of his death, somewhere between 50-80% of all people living in colonial America had heard him speak. His evangelical Great Awakening preaching served as a counterweight to Deism, the other theological movement that helped shape colonial America and the creation of the United States of America.

Due to his long friendship with Jonathan Parsons, Whitefield made several trips to Newburyport — the final one on his life’s last day. On Sept. 29, 1770, he preached outdoors for two hours to 6,000 people in Exeter, New Hampshire. Of that moment he said, “Lord Jesus, I am weary in thy work, but not of it.” Wracked with asthma, Whitefield then returned to Parsons’ home, where he died on Oct. 2. Due to his 30-year connection to the church, his desire to be buried beneath its pulpit was enthusiastically granted.

The legacy of John Wesley and George Whitefield’s preaching is spectacular. Whitefield, “America’s First Celebrity,” preached an estimated 18,000 times from 1735-1770 on both sides of the Atlantic while Wesley focused on the British Isles. Wesley preached an estimated 40,000 times from the 1730s to his death at the age of 88 in 1791.

Lyman, a graduate of Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary and Western Michigan University, is a retired United Methodist pastor of the Michigan Conference now living in Laguna Niguel, California. He continues to preach, write, teach and serves as an Apprenticeship Group leader for Fuller Theological Seminary.

News media contact: Tim Tanton or Joey Butler at (615) 742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.