Key Points:

- In 1966, Capitol Hill Methodist Church in Washington hung a plaque to dedicate a large, beautiful stained-glass window of Jesus to J. Edgar Hoover, who ran the FBI from 1924 to 1972.

- The church’s parking lot is the former site of Hoover’s home from childhood until he was 43 years old.

- After much discussion, the church will rededicate the window at a ceremony on Sept. 29, and the old plaque will be displayed elsewhere in the church, along with an explanation of the circumstances.

When one thinks about Jesus, longtime FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover is unlikely to be the next thought. And vice versa.

But that association does frequently come up at Capitol Hill United Methodist Church in Washington. There’s a huge, beautiful stained-glass window of Jesus in the sanctuary. A plaque nearby dedicates the window to Hoover, who headed the FBI and its predecessor agency from 1924 until his death in 1972. The church parking lot sits on the property where Hoover was born and lived for many years.

Yes, the same Hoover who tried to blackmail the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and insisted for years the mafia didn’t exist. The same Hoover who allegedly possessed files of embarrassing photos and reports of government officials and other victims as insurance to keep him in his position.

“(The plaque) signals to me that you agree that J. Edgar Hoover is a good model for Christian virtues,” said the church’s pastor, the Rev. Stephanie Vader. “Because otherwise, why would you have it up there?”

The congregation plans to address the situation, and hopefully reconcile it, with a Sept. 29 rededication ceremony for the window to distance it from Hoover. The original plaque will be moved elsewhere in the church, along with an explanation of the circumstances.

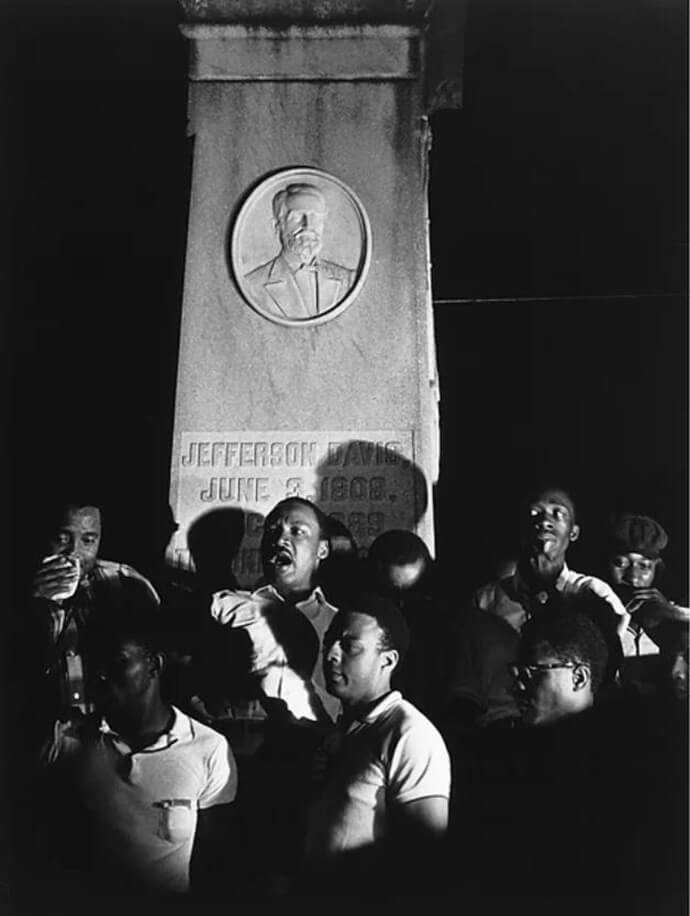

“There was a dedication ceremony in 1966, which Hoover himself attended, along with multiple white bishops, because we were segregated conferences at the time,” Vader explained.

The September event is meant as a counterweight to that June 26, 1966, ceremony.

According to an account by Gale Monro, the church’s archivist, the dedication service featured sermons and prayers by prominent white clergymen who stated that Hoover merited being honored because of his dedication to Christian virtues.

“The Rev. Edward Lewis, the pastor of CHUMC, preached on the scripture passage about the divine calling of the prophet Samuel, who helped turn the nation of Israel back to God from sin and idolatry,” Monro wrote. “(The) Rev. Lewis said that Hoover was a modern Samuel who had heeded God’s call to turn America away from subversion and back to God.”

That’s high praise for a man whose legacy has since been questioned. Hoover gets credit for advancing the FBI technology-wise, but some of his activities were suspect or outright illegal.

“The FBI was spying on student groups and women’s groups and civil rights groups — and not for crimes committed or alleged crimes, but really for their political beliefs,” said Lerone A. Martin, a professor at Stanford University and author of “The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism.”

Today’s Christian nationalism movement, an ideology that the U.S. should be ruled by white evangelical Christians and their beliefs, traces directly to Hoover, Martin said. Hoover was raised a Presbyterian.

“I do believe it’s connected to Hoover,” Martin said. In a webinar for Capitol Hill United Methodist he presented earlier this year, Martin quoted Hoover as saying in 1961 that the FBI has “a Christian purpose … to defend and perpetuate the dignity of the nation’s Christian endowment.

“When Hoover took over the FBI, he was deliberate in making it reflect his white, Christian nationalist views,” Martin said. “He got rid of all the women who were special agents and all of the men of color, as well. He hired exclusively white Catholic and Protestant men to be FBI agents and to be the leadership of his FBI.”

Hoover also used information the FBI collected to pressure politicians and others, Martin added.

“There are documented reports of when the Senate would have to vote for appropriations, that Hoover would send an FBI agent to a congressman and say, ‘We received these photos of your wife doing this, or we have reason to believe that you’re doing this, and we just want you to know that we’re aware of the situation and we’re taking care of it.’

“This was a way to indirectly push for a certain congressman to vote the way the FBI wanted them to vote,” he said.

It’s been documented that Hoover tried to use recordings of King in compromising sexual situations to try to induce him to commit suicide.

All of which makes the plaque recognizing Hoover as a good model for Christian virtues problematic.

Subscribe to our

e-newsletter

“It is the biggest focal point in our sanctuary,” Vader said. “It’s the biggest window. It’s huge.”

Discerning how to address the issue has been “a lengthy process,” said Tamara Rountree, a member of the church and part of its racial justice ministry band.

“This is a very sensitive topic that I don’t think should be rushed or shoved down people’s throats,” Rountree said. “I’m big on educating people and making sure they understand things, so we wanted to give the congregation as much voice in this as possible. It’s been very deliberative.”

The racial justice ministry band meets monthly to discuss the window plaque and other racial issues. Among other activities, the band started a program to pay royalties for Negro spirituals performed in church. This year the money went to the local Duke Ellington School of the Arts.

“We did a lot of discernment within our group,” said church member Steve DeWitt. “We had the youth in our church take a look at the window and study it, and they are the ones who recommended rededicating it.”

The church youth made a video about it.

“One option is we could dedicate it to the CHUMC community,” says one boy in the video. “We want to show support for a community that has supported us, and we want to show that even though Hoover, who wasn’t even a member of the Methodist Church, didn’t support the whole community, we do.”

The willingness of white members of Capitol Hill United Methodist Church to address the issue is significant to the church’s Black members, said church administrator Xavier Hodge.

“We’re all in the same place that we don’t want to be known as a place that honored someone who did so many bad things,” he said.

The issue isn’t whether to forgive Hoover of his lapses, Vader said.

“We can forgive him and (still) take the plaque down,” she said. “There’s been some really powerful moments, like one of our newer members, who is now our lay leader, who’s Black and said she joined a year ago.

“She said, ‘You know, I didn’t even notice the plaque when I was first coming, and I was excited about the church, so I joined. And then I noticed the plaque and I think if I’d noticed it when I first started coming, I wouldn’t have joined.’”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umnews.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.