The road leading up to the 1569 publication of the first complete Bible in Spanish included the Spanish Inquisition, smuggling of banned books in cases marked as wine bottles and a monk chased across Europe by Spanish authorities with murder on their minds.

An Oct. 27 ceremony commemorating the 450th anniversary of the publication of “The Bible of the Bear” won’t have that danger and drama, but will include presentations on the impact of the translation on Christianity.

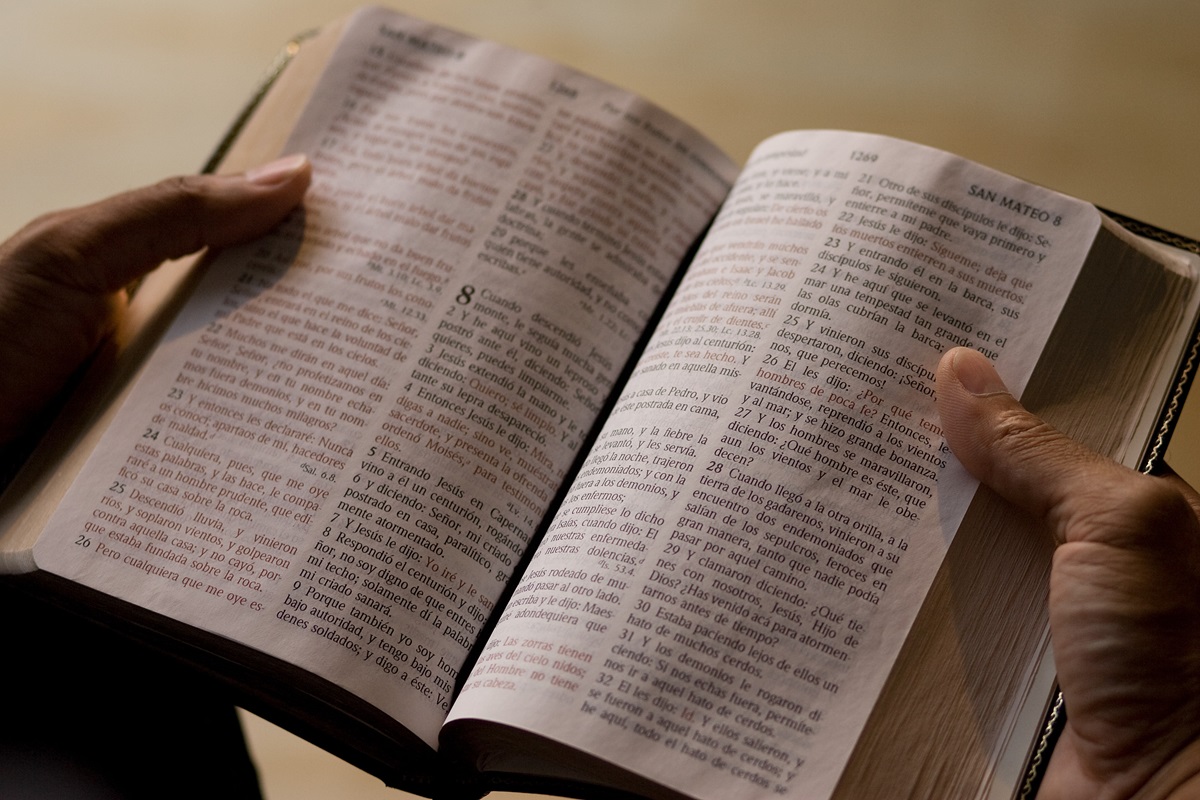

“It’s the Bible that has saved Spanish-speaking Protestants over generations, in its language and its understanding of reality,” said Justo González, a biblical scholar and retired United Methodist pastor.

The prose also compares well with other Spanish literature in what was a golden age that included classics such as “Don Quixote,” González said.

The 4 to 5:30 p.m. ceremony will take place on Reformation Sunday at Oxford United Methodist Church in San Antonio. The service will have Spanish and English portions and will include presentations on the historical, religious, cultural and literary impact of the “The Bible of the Bear” on the Protestant movement in Europe and world Christianity.

“The program will include a procession of children with Bibles from several congregations at the beginning of the service,” said Bishop Joel Martinez, who retired in 2008 as bishop of the San Antonio area.

“The program will include a procession of children with Bibles from several congregations at the beginning of the service,” said Bishop Joel Martinez, who retired in 2008 as bishop of the San Antonio area.

Erika Prosper Nirenberg, first lady of San Antonio and a United Methodist, will offer greetings, and there will be speakers from other faiths. A new hymn by Raquel Mora Martinez, editor of the Spanish-language United Methodist Hymnal, will be performed.

The story of the Spanish Bible began in the 16th century at the Monastery of St. Isidore of the Fields, located outside of Seville, Spain, where Casiodoro de Reina was a monk in the Order of St. Jerome. In the early sixth century, St. Jerome himself was a Bible translator.

Reina and the other monks learned about the Protestant movement started by Martin Luther in 1517, González said.

“They began learning what was going on outside of France, mostly through a man who with his mother brought books into Spain in what were supposed to be wine bottles,” González said. “This man stopped at this convent, and many of the monks were impressed by him. Then one day the (Spanish) Inquisition got hold of him and burned him.”

The monks started Bible studies in and around Seville and also explored the possibility of translating the Scriptures into the vernacular of the time. These were reformation ideas encouraging laity to participate in faith formation by having access to the Scriptures, Martinez said.

Bibles available in Spain were only in Latin, which most people could not read. The idea that common people could read the Bible and discern its lessons without guidance from church authorities was threatening to church leaders, said Rafael Serrano, author of “The History of the Spanish Bible” and senior director of Latin American Ministries at Bible League International.

“Those people (who studied the Bible on their own) were taken to the Spanish Inquisition and they were killed, burned at the stake and the writers were burned, too,” Serrano said. “But Casiodoro de Reina was influenced by them, and also they received some books and publications from (Martin) Luther, and he became sympathetic for Lutherans.”

Fearing the Spanish Inquisition, the monks in the Monastery of St. Isidore of the Fields fled in different directions, pledging to meet in one year in Geneva, Switzerland. Reina and fellow monk Cipriano de Valera, who would later edit Reina’s translation, were among those who kept that commitment.

“Geneva was getting more and more strict and finally they burned Michael Servetus, the Spanish doctor who was considered a heretic by Protestants and Catholics,” González said. “Casiodoro de Reina left and went to various places, ending up in England.”

Reina got married in England and became pastor of a church. The Spanish ambassador there alerted King Phillip of Spain that Reina was still working on a Bible translation.

“(King Phillip) sent them a message that by hook or by crook make sure he leaves so we can catch him and bring him back to the Inquisition where he belongs,” González said. “They accused him of sodomy … and it was a capital offense and so he had to flee.”

Warned of his impending arrest, Reina abruptly left his wife and Bible translation work and fled to Flanders, Belgium. Disguised as a sailor, his wife later escaped and joined him.

A bishop in the Anglican Church saved the translation project by gathering Reina’s papers and shipping them to him in Flanders.

Reina focused on the Old Testament, because a Spanish version of the New Testament had been published in Spain.

Reina focused on the Old Testament, because a Spanish version of the New Testament had been published in Spain.

“When he was finishing the Old Testament and the printing was almost complete, they learned that the entire edition of the New Testament had been confiscated … and burned,” González said.

So Reina translated the New Testament as quickly as he could, handing the copy over page by page as the printer waited.

“It was quite an accomplishment,” González said. “First of all you step back and think that this work done in such haste has been hailed as part of the classical Spanish literature.”

The accuracy of Reina’s Bible was “very good for his time,” Serrano said.

“That’s because he used the earliest manuscripts he could get,” Serrano said. “For example, for the New Testament, he went from Erasmus’ Greek New Testament.”

For the Old Testament, Reina consulted Jewish scholars.

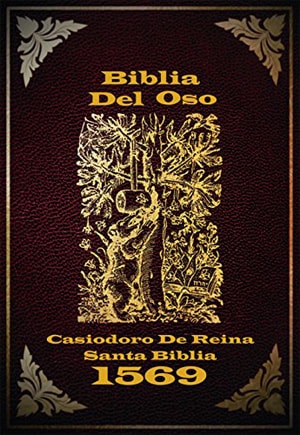

One mystery remains — the illustration of a bear reaching for a pot of honey on the cover that resulted in the name “The Bible of the Bear.”

“That’s been debated,” González said. “There’s a reference in Proverbs about ‘sweet to my mouth is your word like honey.’ That’s one theory,” he said.

The other theory is the printer had the illustration on hand, he said.

Serrano also believes the illustration was something the printer conveniently had around but wishes there were a better story about the cover.

“The Bible is so sweet like honey, no?” he said. “It was marketing in the 16th century.”

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

Patterson is a UM News reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact him at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.

An Oct. 27 ceremony commemorating the 450th anniversary of the publication of “The Bible of the Bear” won’t have that danger and drama, but will include presentations on the impact of the translation on Christianity.

“It’s the Bible that has saved Spanish-speaking Protestants over generations, in its language and its understanding of reality,” said Justo González, a biblical scholar and retired United Methodist pastor.

The prose also compares well with other Spanish literature in what was a golden age that included classics such as “Don Quixote,” González said.

The 4 to 5:30 p.m. ceremony will take place on Reformation Sunday at Oxford United Methodist Church in San Antonio. The service will have Spanish and English portions and will include presentations on the historical, religious, cultural and literary impact of the “The Bible of the Bear” on the Protestant movement in Europe and world Christianity.

United Methodist Bishop Joel N. Martinez

Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS

Photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS

Erika Prosper Nirenberg, first lady of San Antonio and a United Methodist, will offer greetings, and there will be speakers from other faiths. A new hymn by Raquel Mora Martinez, editor of the Spanish-language United Methodist Hymnal, will be performed.

The story of the Spanish Bible began in the 16th century at the Monastery of St. Isidore of the Fields, located outside of Seville, Spain, where Casiodoro de Reina was a monk in the Order of St. Jerome. In the early sixth century, St. Jerome himself was a Bible translator.

Reina and the other monks learned about the Protestant movement started by Martin Luther in 1517, González said.

“They began learning what was going on outside of France, mostly through a man who with his mother brought books into Spain in what were supposed to be wine bottles,” González said. “This man stopped at this convent, and many of the monks were impressed by him. Then one day the (Spanish) Inquisition got hold of him and burned him.”

The monks started Bible studies in and around Seville and also explored the possibility of translating the Scriptures into the vernacular of the time. These were reformation ideas encouraging laity to participate in faith formation by having access to the Scriptures, Martinez said.

Bibles available in Spain were only in Latin, which most people could not read. The idea that common people could read the Bible and discern its lessons without guidance from church authorities was threatening to church leaders, said Rafael Serrano, author of “The History of the Spanish Bible” and senior director of Latin American Ministries at Bible League International.

“Those people (who studied the Bible on their own) were taken to the Spanish Inquisition and they were killed, burned at the stake and the writers were burned, too,” Serrano said. “But Casiodoro de Reina was influenced by them, and also they received some books and publications from (Martin) Luther, and he became sympathetic for Lutherans.”

Fearing the Spanish Inquisition, the monks in the Monastery of St. Isidore of the Fields fled in different directions, pledging to meet in one year in Geneva, Switzerland. Reina and fellow monk Cipriano de Valera, who would later edit Reina’s translation, were among those who kept that commitment.

“Geneva was getting more and more strict and finally they burned Michael Servetus, the Spanish doctor who was considered a heretic by Protestants and Catholics,” González said. “Casiodoro de Reina left and went to various places, ending up in England.”

Reina got married in England and became pastor of a church. The Spanish ambassador there alerted King Phillip of Spain that Reina was still working on a Bible translation.

“(King Phillip) sent them a message that by hook or by crook make sure he leaves so we can catch him and bring him back to the Inquisition where he belongs,” González said. “They accused him of sodomy … and it was a capital offense and so he had to flee.”

Warned of his impending arrest, Reina abruptly left his wife and Bible translation work and fled to Flanders, Belgium. Disguised as a sailor, his wife later escaped and joined him.

A bishop in the Anglican Church saved the translation project by gathering Reina’s papers and shipping them to him in Flanders.

Cover of La Biblia del Oso

Courtesy of Bishop Joel N. Martinez

Courtesy of Bishop Joel N. Martinez

“When he was finishing the Old Testament and the printing was almost complete, they learned that the entire edition of the New Testament had been confiscated … and burned,” González said.

So Reina translated the New Testament as quickly as he could, handing the copy over page by page as the printer waited.

“It was quite an accomplishment,” González said. “First of all you step back and think that this work done in such haste has been hailed as part of the classical Spanish literature.”

The accuracy of Reina’s Bible was “very good for his time,” Serrano said.

“That’s because he used the earliest manuscripts he could get,” Serrano said. “For example, for the New Testament, he went from Erasmus’ Greek New Testament.”

For the Old Testament, Reina consulted Jewish scholars.

One mystery remains — the illustration of a bear reaching for a pot of honey on the cover that resulted in the name “The Bible of the Bear.”

“That’s been debated,” González said. “There’s a reference in Proverbs about ‘sweet to my mouth is your word like honey.’ That’s one theory,” he said.

The other theory is the printer had the illustration on hand, he said.

Serrano also believes the illustration was something the printer conveniently had around but wishes there were a better story about the cover.

“The Bible is so sweet like honey, no?” he said. “It was marketing in the 16th century.”

Bishop Joel N. Martinez blesses the elements of Holy Communion during opening worship at the 2011 MARCHA meeting at the Lydia Patterson Institute in El Paso, Texas. File photo by Mike DuBose, UMNS.

Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.