For decades after her execution on April 29, 1968, it appeared that the Chinese Communist Party had silenced Lin Zhao, a slight but iron-willed Christian poet and essayist who dared speak truth to power in the face of imprisonment and torture.

Miraculously, it hasn’t worked out that way.

Written by Duke Divinity School Professor Lian Xi, “Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao’s China,” tells the story of the Methodist-educated martyr. The tale is a thriller, with Lin Zhao the near-unbelievably courageous hero, writing criticisms of the government with her own blood on clothing and bedsheets when prison guards deprived her of pen and paper.

“Blood Letters,” published by Basic Books, has received strong reviews in such publications as the Atlantic, the New York Review of Books, Christianity Today and Christian Century.

Kirkus Reviews called it “a moving account of astonishing human courage in the leering face of human cruelty.”

Nearly 40 years after Lin Zhao was declared innocent of the crimes that led to her murder, the Chinese government is again trying to intimidate those inspired by her story. Every April, on the anniversary of her death, admirers travel to her tomb in the Lingyanshan Cemetery near Suzhou in the Jiangsu Province.

In recent years, the government has put up a locked fence, intimidated and sometimes arrested the visitors.

“Her voice still speaks to the people’s aspiration for freedom and human dignity, and that’s why they started to clamp down,” said Lian Xi, professor of world Christianity at Duke.

Lin Zhao’s journey was not a straight line. Born to educated, upper middle-class parents, she embraced the Communist revolution despite the trouble it caused her family. And she did her part for the Communists as they demonized and sometimes murdered landholders during the land reform era. But Lin Zhao’s stubborn nature and idealism led her away from her initial idealization of Mao Tse-Tung.

Speaking up cost her freedom, and ultimately her life.

In a final insult, Lin Zhao’s family was billed half a yuan (roughly 7 cents) for the bullet used to kill the 36-year-old activist.

“There certainly will be those who refuse to change until they die,” Mao wrote about the harassment and murder of political dissenters. “They are willing to go see God carrying their granite heads on their shoulders. That will be of little consequence.”

Why were party leaders so threatened by Lin Zhao speaking her mind on politics in the late 1950s and 1960s? And why are their successors threatened today?

“She inspires people in search of a better society. She also challenges the legitimacy of the Communist government, and they care deeply about their political legitimacy,” Lian Xi said.

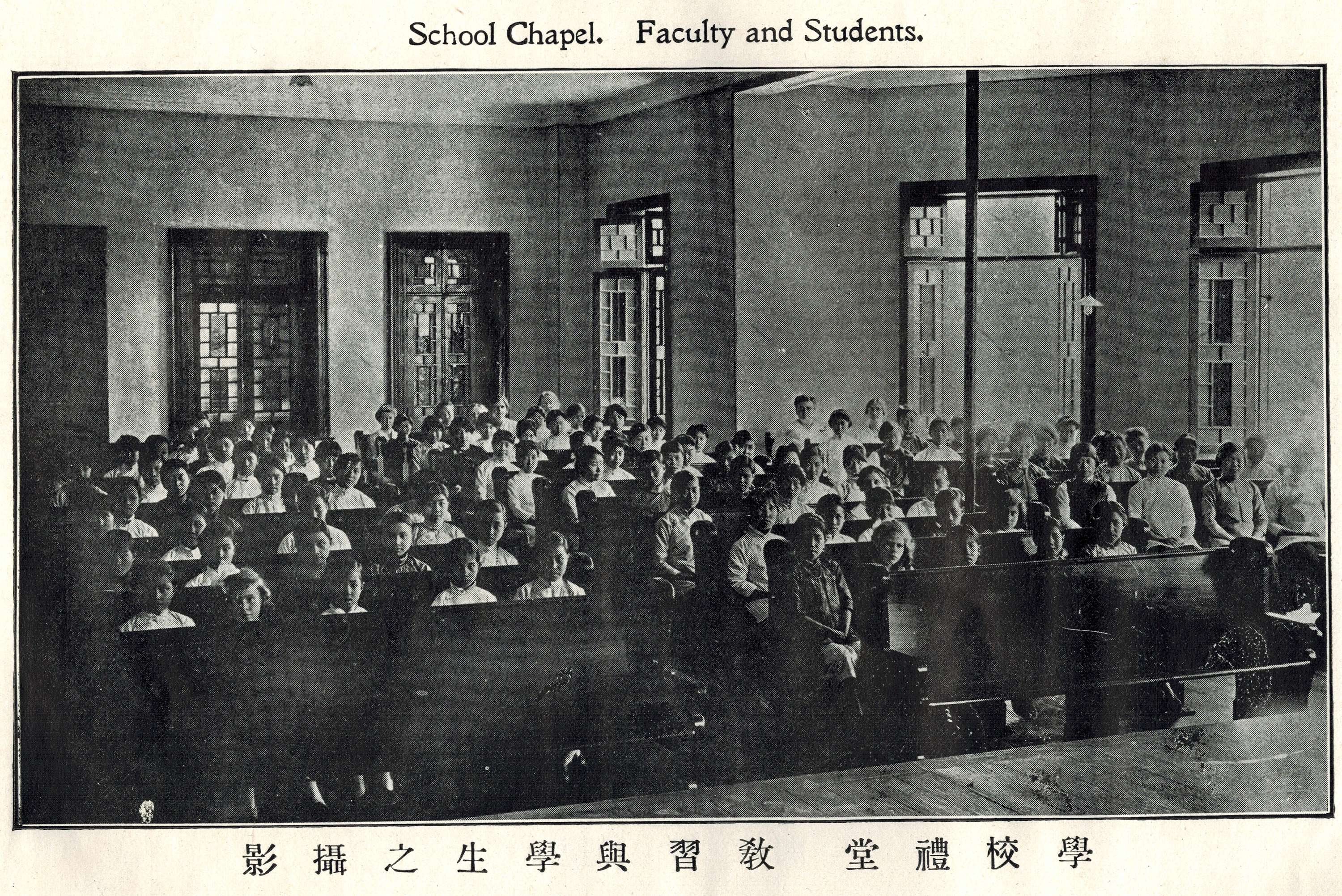

As a teenager, Lin Zhao was heavily influenced by Christian values she learned at the Laura Haygood Memorial School for Girls, which she attended for two years. The school was founded in honor of Haygood (1845-1900), an early Methodist Episcopal Church South missionary to Asia.

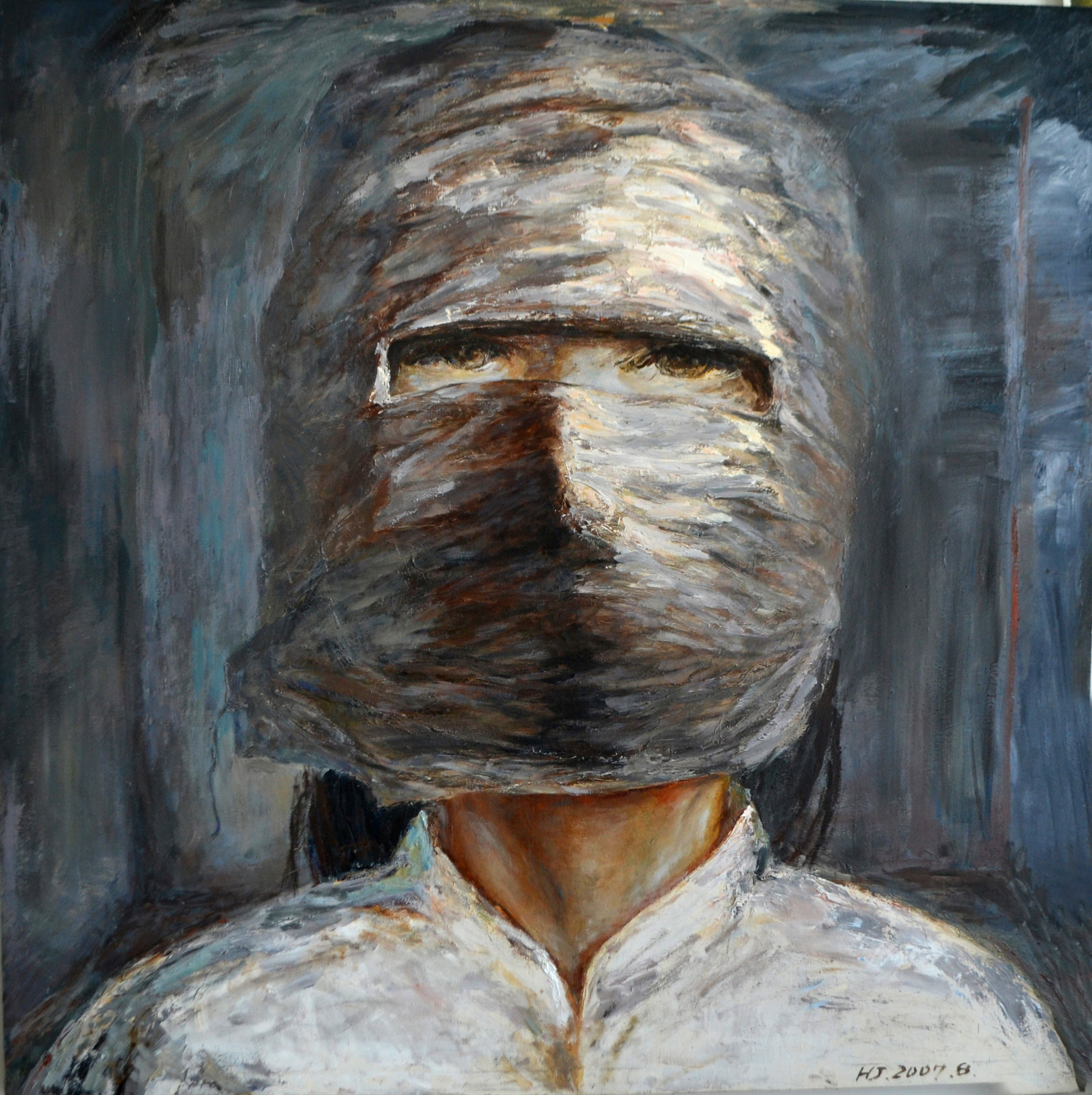

authorities in 1968. Photo courtesy of Lian Xi.

“It was a transformative period,” Lian Xi said of Lin Zhao’s time at the school. “It shaped her in profound ways.” Two decades after she had completed her studies, she held on to the Biblical verses, hymns and stories she learned there, even as she was imprisoned and tortured.

“She sank religious roots much deeper than she realized at the time,” Lian Xi said. “One of the hallmarks of the Methodist work – both Southern and Northern Methodists – was to preach a holistic gospel. It was not just about the saving of individual souls. It was also about transforming Chinese society, about liberating people from the bondage of semi-slavery and the things that had held people back.”

Lin Zhao drifted from organized religion as a young woman, although there is no evidence she ever lost her Christian faith. She joined the Communist Party for a short while before being expelled for disobeying orders. Still, she participated in the land reform program under Mao. Her work didn’t include the torture and killing of landlords, but she was part of the system that resulted in executions.

“Even though I do not have blood on my hands, I must have been splashed with blood,” Lin Zhao wrote, as quoted in “Blood Letters.”

Lin Zhao grew disenchanted with communism’s failure to match its rhetoric. She was crestfallen by the corruption of the local communist officials she dealt with.

To learn more about Lin Zhao

“She had a fiery temperament,” Lian Xi said. “Throughout her life you find a streak — a very strong one — of independence in her.”

Lin Zhao was one of many activists caught in a Mao trap called the Hundred Flowers Movement. The movement invited criticism of the Communist Party to “help improve the party’s work.”

Lin Zhao, a student at Peking University at the time, spoke her mind. But Mao’s request for criticism wasn’t sincere.

“Let all these ox devils and snake demons … curse us for a few months,” Mao said, as reported in “Blood Letters.” “One day punishment will come down on their heads.”

Many who spoke out ended up in jail or dead. Lin Zhao was first arrested in 1960.

In prison, she was manhandled and beaten by guards. There were suicide attempts and hunger strikes. In her writings, Lin Zhao said she had “lost track of how much hair (one guard) pulled off my head.”

Such treatment did not deter Lin Zhao. She developed an ingenious technique to continue writing. She would prick one of her fingers with a bamboo pick, hair clip or the plastic tip of her toothbrush after she had sharpened it on the concrete floor. She collected the resulting blood in a plastic spoon and would dip her makeshift pen — either a thin bamboo stick or a straw stem — and write in blood on shirts or torn bedsheets.

Lin Zhao would then copy the blood writings with pen and paper when authorities allowed her access to them again.

Nanjing, China, in this undated file photo. He intended to pay tribute to dissident Lin Zhao,

who was executed in 1968. He was arrested by Chinese authorities and is still in custody as

of October 2018. Photo courtesy of Lian Xi.

“As a Christian, my life belongs to my God,” Lin Zhao wrote in a letter intended for the Communist newspaper “People’s Daily.” “I have come to see more clearly and deeply the many terrifying and shocking evils committed by your demon political party! … I cried for your blood-smeared words, which are unable to rid themselves of evil and are dragged by its terrifying weight ever deeper into the swamp of death.”

Prison authorities confiscated her poems and essays, but she believed her work would eventually be seen by others. She was right. Prison authorities kept the writings in case they were needed as evidence against Lin Zhao. When the government absolved her in the early 1980s, some writings were released to her family. Others remain under lock and key by the government.

“Portions of her writings have been published on the internet since the early 2000s,” Lian Xi said. “It’s really become a Promethean fire to contemporary Chinese dissent.”

Filmmaker Hu Jie made the 2004 documentary “Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul” —sporadically viewable on YouTube. Lian Xi saw the film in 2011, and the next year traveled to the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where some of Lin Zhao’s papers are collected. In 2013, he was gifted with a printed copy of some of Lin Zhao’s work. All this led to the writing and publication of “Blood Letters.”

With the release of the book this year, Lin Zhao’s story continues to spread. Asked if there is any interest from Hollywood to Lin Zhao’s story, Lian Xi demurs.

“I’d better not comment on this right now,” he said.

In an unsettling parallel, activist Zhu Chengzhi was arrested in April of 2018, as he tried to reach Lin Zhao’s tomb to observe the 50th anniversary of her death.

He has not been heard from since.

Patterson is a United Methodist News Service reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Contact Patterson at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org. To read more United Methodist news, subscribe to the free Daily or Weekly Digests.Like what you're reading? Support the ministry of UM News! Your support ensures the latest denominational news, dynamic stories and informative articles will continue to connect our global community. Make a tax-deductible donation at ResourceUMC.org/GiveUMCom.